(This blog is based on a working paper, which also includes a bit of modeling for a textbook market with multiple sellers, varying levels of perceived quality, and copyright enforcement. The full text of the paper is here, and comments are appreciated.)

(This blog is based on a working paper, which also includes a bit of modeling for a textbook market with multiple sellers, varying levels of perceived quality, and copyright enforcement. The full text of the paper is here, and comments are appreciated.)

In the early 2000s, the International Intellectual Property Association complained that large scale piracy of textbooks was common in Panama. It sought the intervention of U.S. trade officials, noting that “the major forms of piracy afflicting the U.S. book publishing industry in the region involve commercial photocopying piracy.” Panama was engaged in various trade negotiations with the U.S. in the early-to-mid 2000s (first as part of the failed Free Trade Area of the Americas, then as a party to bilateral trade agreement negotiations which were ultimately successful), giving the U.S. leverage to seek policy changes regarding the enforcement of copyrights.

Following interventions by the U.S., Panama strengthened enforcement of copyrights in the mid-2000s. Laws passed in 2003, 2004 and 2007 increased civil and criminal penalties for both large scale and small scale infringement. Additional administrative rules at the federal level were enacted in 2006.[1] With support from the U.S. State Department, Panama held a series of trainings for police officers and judges to teach them to enforce the laws more strongly. Panama’s improved enforcement of copyrights over this period was reported by the U.S. Trade Representative in its annual Special 301 Review of other countries’ intellectual property law, and by the World Trade Organization in its 2007 Trade Policy Review.

Data from the World Bank Living Standards Measurement Survey (LSMS) can be used to show the impact on how students obtained – or failed to obtain – textbooks after the increase in copyright enforcement.

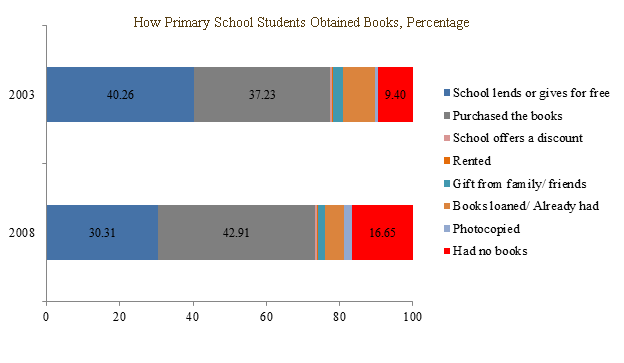

The surveys were conducted in 2003 and 2008 in Panama, before and after the policy change. For each individual of primary school age within the household, data was collected on how they obtained, or failed to obtain textbooks. Those who purchased books were asked how much they spent. (There is also data on secondary school and university students, but this post sticks to the data on primary school students.)

People who purchased books spent 49% more in 2008 than people who purchased books in 2003. This increase exceeded overall inflation, which was about 10%. However, the data is does not differentiate between new books, secondhand books, or purchased copies. It provides a birds eye view that shows people paid more, but it does not indicate the price hike for new books.

The more interesting data is the breakdown of responses to the question of how students obtained books:

- More kids had books purchased by their families

- Fewer kids received books from their schools

- Fewer kids received books through other means (loans, friends, etc)

- On balance, more kids were unable to receive books.

Here is the breakdown of the data:

| HOW STUDENTS OBTAINED BOOKS (%) | 2003 | 2008 | Change |

| Had no books | 9.40 | 16.65 | 7.25 |

| Books loaned/ Already had | 8.86 | 5.26 | -3.60 |

| Gift from family/ friends | 2.71 | 2.00 | -0.71 |

| School lends or gives for free | 40.26 | 30.31 | -9.95 |

| School offers a discount | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.15 |

| Purchased the books | 37.23 | 42.91 | 5.68 |

| Rented | 0.24 | 0.18 | -0.06 |

| Photocopied | 0.83 | 2.07 | 1.24 |

| N | 3,723 | 3,952 |

And here is the graphic presentation of it:

Two points can be made based on the data. First, prices were observed to rise, and to rise more quickly than overall consumer goods. This shows the expected positive relationship between intellectual property enforcement and prices. Though the available data does not provide a detailed account of the prices paid in different transactions, it does demonstrate at the birds-eye level that those who purchased books paid higher prices.

Second, an increase in enforcement was followed by changes in how students obtained, or failed to obtain textbooks in Panama. Most students either obtained books freely from their school, purchased books out of pocket, or failed to obtain them at all. After the policy change, there was an increase of students purchasing books at higher prices, but this was offset by a larger decrease in the percentage of students obtaining books from their schools. The percentage of students without access to textbooks rose from 9% to 17%.

———————————————–

[1] Resolution No. 013 of 9 March 2006, cited as proof of stronger copyright enforcement in the WTO Trade Policy Review, 2012.