The U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) is currently investigating “Indian industrial policies that discriminate against U.S. imports… and the effect those barriers have on the U.S. economy and U.S. jobs.” The investigation was requested by Sen. Hatch, Sen. Baucus, Rep. Camp, and Rep. Levin, and the final report is due to be released in November. Last week it held a series of hearings, where it heard from U.S. business, Indian business, and civil society representatives.

The U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) is currently investigating “Indian industrial policies that discriminate against U.S. imports… and the effect those barriers have on the U.S. economy and U.S. jobs.” The investigation was requested by Sen. Hatch, Sen. Baucus, Rep. Camp, and Rep. Levin, and the final report is due to be released in November. Last week it held a series of hearings, where it heard from U.S. business, Indian business, and civil society representatives.

I’ve posted notes on the thee panels here, here, and here. KEI has videos of the hearings here.

Much of the debate centered on the experiences of the U.S. drug industry in India. Some witnesses said the U.S. industry is doing well. Ron Summers from the U.S.-India Business Council said that firms are “thriving.” D.G. Shah from the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance described partnerships between Indian and American firms that are working well for both sides. Pharmaceutical industry representatives were much more pessimistic. Rod Hunter from PhRMA and Julie Corcoran from both said that Indian IP policies had hurt their companies. One particular policy measure that received a lot of attention was the compulsory license issued on Bayer’s anticancer drug Nexaver.

The Commissioners repeatedly asked for empirical evidence regarding Indian policies and their effects that these policies have had on American companies. Below I’ve posted a few graphics to show that the experience of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry has been largely positive. They are followed by one graphic comparing prices offered by Bayer and (Indian generic firm) Natco to Indian income by quintile.

U.S. pharmaceutical exports have been steadily rising

Source: World Trade Organization

Source: World Trade Organization

According to trade data from the World Trade Organization, U.S. pharmaceutical exports rose from $39 million to $225 million during the period 2000-2012. This is an increase of 470%.

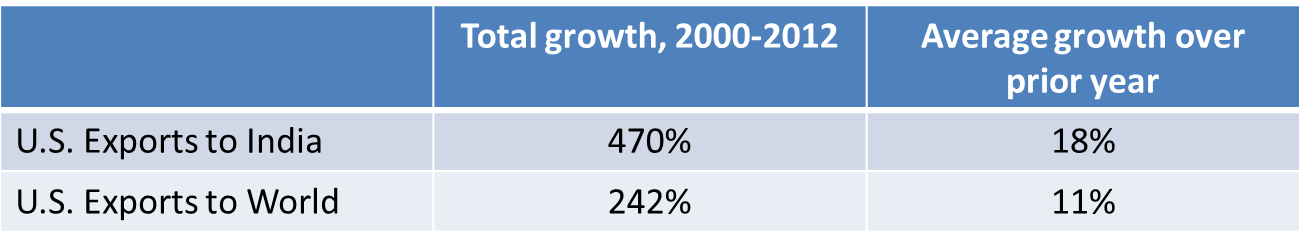

Exports to India are growing more rapidly than exports elsewhere

Furthermore, U.S. pharmaceutical exports to India are growing at a faster rate than U.S. pharmaceutical exports to the world as a whole. Since the Patents Act was amended in 2005, export growth in India has outpaced overall world growth in six out of eight years.

Source: World Trade Organziation

Source: World Trade Organziation

Source: World Trade Organization

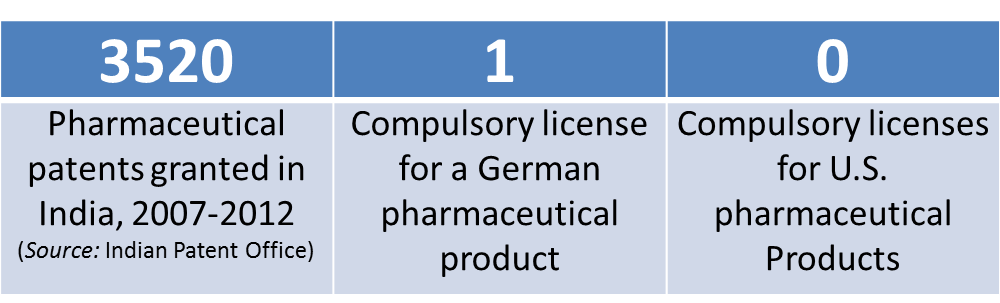

Many pharmaceutical patents are granted, and there has been one compulsory license to date

It is notable that there has not been a single compulsory license granted on an American product. The ITC has been instructed to investigate the effect of Indian policies on the U.S. economy. Similarly, the Special 301 Review led by USTR is supposed to investigate the effect of IP policies on “U.S. persons who rely on intellectual property protection.” But the one compulsory license issued has been on a patent held by Bayer, a German firm.

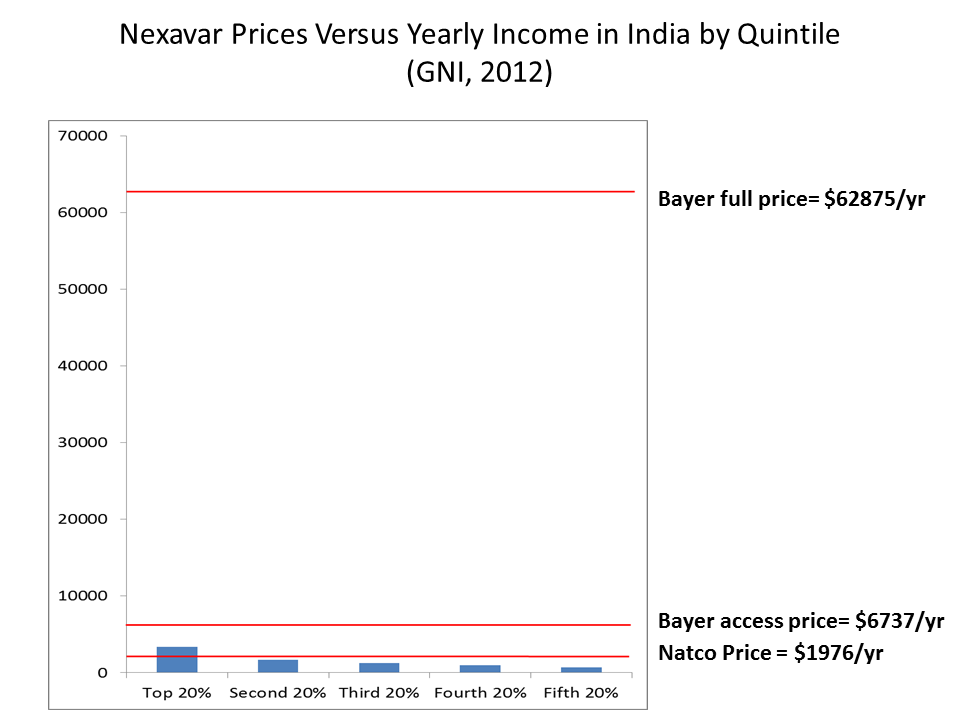

Bayer’s market price and “access price” for Nexavar were both unaffordable to most of the Indian population

At last week’s ITC hearings, representatives from Bayer, the National Association of Manufacturers, and others, noted that Bayer was making the drug available at a lower “access price” in India. However, if one converts the full price and access price to U.S. dollars (based on a January 2013 exchange rate) and compares them to the average annual income-by-quintile, the data shows that both prices exceed annual income of even the top 20%.

Sources: Income and income distribution data from World Bank; Prices from the Nexaver compulsory license

Sources: Income and income distribution data from World Bank; Prices from the Nexaver compulsory license