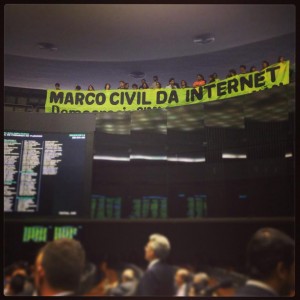

Photo: Bruno Lewicki

Luiz Fernando Moncau (@lfmoncau)

Pedro Nicoletti Mizukami (@p_mizukami)

Center for Technology and Society @ FGV Law School, Rio

At around 9pm today, March 25th 2014, the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies finally voted in favor of approving the Marco Civil bill. The text, which can be read here (in Portuguese), will now be sent to the Federal Senate for deliberation. If any changes are approved there, it will be returned to the Chamber of Deputies before it can be sanctioned by President Dilma Rousseff.

Marco Civil, which is the first major Brazilian law on Internet rights—including provisions on net neutrality and intermediary liability—was modified several times by rapporteur Dep. Alessandro Molon (Worker’s Party, Rio de Janeiro), so that consensus could be reached in the Chamber of Deputies. It was a complicated process.

The approved text is substantially different than the version sent to Congress in 2011, which was the output of a broad public consultation process that took place between October 2009 and May 2010 (more information can be found in the 2011 CGI.Br Internet Policy Report). Battles over intermediary liability, data retention, and net neutrality stalled bill’s progress in the Chamber of Deputies for more than two years. Voting was delayed successive times even after the bill was put under urgency regime in September 2013—a status that has the effect of blocking most other proposals until voting is carried out.

Considering how terrible some of the proposed amendments to Marco Civil were, the approved text is largely positive. It is definitely not the ideal version of law. But it is a much better one than expected, and probably the best possible outcome given the existing political limitations.

Here is a short summary on some of the most important items:

Data retention

Brazil was dangerously close to establishing a period of 5 years of mandatory data retention before discussions on Marco Civil began. Unfortunately, the bill still has provisions to that effect, but the period is much shorter for ISPs providing connectivity services (1 year). The bad news is that mainly due to aggressive pressure by the Federal Police, other Internet services—initially excluded from Marco Civil—are also subject to data retention (6 months).

Net neutrality

Brazil has taken a major step forward in preserving net neutrality, following the example set by countries such as Chile and the Netherlands. Marco Civil establishes the general principle that net neutrality should be guaranteed, and further regulated by a presidential decree, with inputs from both the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (CGI.br) and ANATEL, the national telecommunications agency. Since telcos have a strong presence at ANATEL, the solution adopted by Marco Civil is arguably the best outcome, even if there is the danger of ineffective regulation further down the road.

Intermediary liability

One of the main provisions of Marco Civil deals with the difficult subject of intermediary liability due to content uploaded by third parties. The system in Marco Civil establishes that intermediaries can only be held liable if they do not comply with a court order explicitly demanding content to be removed. This regime, however, is not applicable to copyright infringement, which will be dealt with by the forthcoming copyright reform bill.

Privacy

After the Snowden leaks, a small number of privacy provisions were included in Marco Civil (the main privacy and data protection bill under development has yet to be sent to Congress). The main proposal was extremely controversial: forcing Internet companies to host data pertaining to Brazilian nations within Brazilian territory. Broadly rejected by civil society, engineers, companies, and several legislators, the proposal was dropped by the government so that voting could take place.

Rights and principles

Marco Civil establishes a strong, forward-looking assertion of rights and principles for Internet regulation in Brazil: freedom of expression, interoperability, the use of open standards and technology, protection of personal data, accessibility, multistakeholder governance, open government data. These provisions usually receive less exposure in media than the ones pertaining to more controversial topics. When taken as a whole, however, they express a strong commitment to an Internet that is an open, collaborative, democratic, space for individual and collective expression, as well as for access to knowledge, culture and information.

Marco Civil will now be discussed in the Federal Senate. If changes are approved there, it will be returned to the Chamber of Deputies, which has the final word on the text.

All in all, this is a major victory for civil society and Internet activists. It was long, difficult process, and there were many occasions when it seemed almost inevitable that the entire bill would be rejected. Now, there is even the possibility that Marco Civil will be passed into law before the NETmundial meeting.

luiz dot moncau at fgv dot br

pedro dot mizukami at fgv dot br