Sean Flynn and Michael Palmedo

Sean Flynn and Michael Palmedo

PIJIP Working Paper 2017-03

Introduction: Copyright law is the subject of increasingly contested debates around the world. Much of this reform is being driven by a perceived need to adapt outdated copyright laws to the digital age. Copyright owners often advocate that these reforms should center on expanding the length, scope, and enforceability of exclusive rights. However, there is a growing recognition that the digital environment warrants expansions in so-called user rights – rights to use copyrighted material without the permission of owners to facilitate a range of modern activities from social media to Internet search.

Few empirical studies analyze the impact of different ways to expand user rights for the digital environment. Should we designate specific digital activities – like indexing, or linking or forwarding an email – that are lawful? Alternatively, should we adopt broader principles of fairness that can be applied to new uses over time? Some theories suggest the second option – adoption of user rights that are more open to unforeseen purposes subject to a flexible test of the fairness – is better for enabling innovation and many modern creative practices. But the existing empirical literature on copyright says little about whether more open and flexible or closed and narrow user rights are in fact better for the core purposes of copyright such as promoting innovation and creativity.

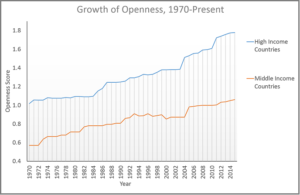

One reason for the lack of empirical research on the impact of more open and flexible user rights has been the absence of a tool to measure changes in this variable of the law. To promote additional and enhanced research into the impact of user rights, we created the User Rights Database. The User Rights Database is an open access repository of coded data showing how and when copyright user rights have changed over time in a representative sample of different countries. The twenty-one countries in our database thus far (with more coming), are split evenly between developing and wealthy countries and are representative of every major region and copyright legal family. The data documents changes in user right openness and flexibility in each country over a period stretching from 1970 to 2016.

We have begun to use the User Rights Database in empirical research projects. The first insight we draw is that there is a general trend toward more open user rights over time in all of the countries. Civil as well as common law systems, for example, have ample experience with exceptions that are openly applicable to any work, for any use, and by any user subject to a flexible “fair use” or “fair practice” balancing test. It is not true that only common law countries can or do implement open and flexible exceptions. That is not to say all countries are the same. More exceptions that are open are unequally distributed. Developing countries in our sample are now at the level of openness that existed in the wealthy countries about thirty years ago.

Another insight from our data is that very few countries have sufficient user rights most needed to support creativity and innovation in the digital economy. These crucial digital exceptions include those permitting transformative and non-expressive uses, including for text- and data-mining. Countries with an open general exception, such as the U.S. fair use right, have been quickest to authorize these new uses.

We used the database in a series of econometric tests. Our data supports the existing theoretical literature that suggests that more open user rights promote innovation and creativity. Namely, we find:

- More open user rights environments are associated with higher firm revenues in information industries, including software, and computer systems design.

- More open user rights environments are not associated with harm to industries known to rely upon copyright protection, such as publishing and entertainment.

- Researchers in countries with more open user rights environments produce more scholarly output and more high-quality output.

The rest of this paper describes our hypotheses, methodologies and results in more detail. Section II surveys the existing theoretical literature that suggests that more open user rights promote innovation and creativity. Section III describes the methodologies we used to construct the User Rights Database. Section IV reports the findings of our econometric analysis.

Click here for the full working paper

Further resources

- Handout summarizing the paper’s findings: English | Portuguese

- Copyright User Rights Database

- PIJIP Copyright User Rights Survey