Mehtab Khan

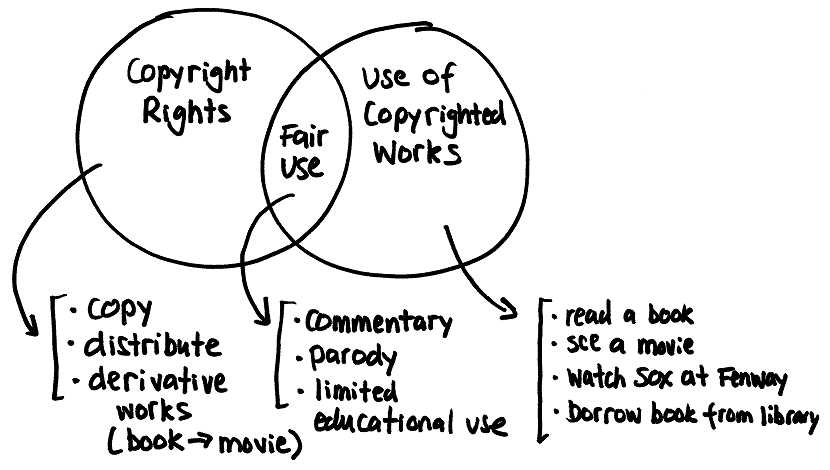

The pandemic has put several pressures on the scope of fair use. Within a matter of weeks, millions of people lost physical access that they normally would have had through libraries and cultural institutions. Fair use was built to be flexible for circumstances like these. But now that users have changed the way that they are accessing copyrighted works, primarily through intermediaries, this has implicated copyright and fair use in novel ways.

Intermediaries include entities like online platforms (both for profit and not-for-profit), large publishers, as well as cultural and educational institutions. Users are now increasingly reliant on intermediaries to provide them access, both in “normal” circumstances, and more so during a pandemic. However, it’s not always clear how fair use applies to the intermediaries impacting end user access, and this lack of clarity is becoming more apparent during the pandemic.

Adapting to online learning and teaching has been a challenge for students and educational institutions during the pandemic. This has prompted many intermediaries to consolidate and make available large troves of copyrighted works. For example, a consortium of universities has partnered with the HathiTrust Digital Library to establish the Emergency Temporary Access Service to allow patrons to “check out” digital scans of books. The Internet Archive has made available 1.4 million copyrighted books for free through the National Emergency Library (NEL). The Internet Archive used to implement a one-reader-at-a-time policy before the pandemic, but there are no such restrictions on the NEL.

These are clear steps to push the bounds of fair use and adapt to an emergency situation. However, this has prompted backlash from stakeholders like authors and publishers. The Internet Archive was recently sued by large publishers such as Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, and Wiley, accusing it of mass copyright infringement. The Author’s Guild and other organizations are insisting that initiatives like the NEL will impact authors’ livelihoods. Their concern is that the Internet Archive is creating a market substitute for books in its collection.

The Internet Archive is not the only intermediary implicated in fair use issues prompted by the pandemic. YouTube, which implements a notice and takedown regime for copyright infringement requests, has been taking down content that should be fair use. Instructors have been receiving copyright notices after posting lectures on large platforms like YouTube. The question here is whether it’s fair use to read materials aloud via video calls, or post recorded versions on YouTube. Many argue that these activities are fair use, while others say that reading aloud is only allowed in a physical classroom. The end result is that intermediaries like YouTube are faced with content moderation decisions which may end up narrowing the scope of fair use in an emergency. Without the ability to access physical classrooms, and sometimes regular internet, some students rely on pre-uploaded lecture videos on YouTube. The decision to take these lectures down without a thorough assessment of whether it’s fair use leaves these students without access.

These incidents have renewed debates about the scope of fair use specifically during an emergency situation. Within these debates, an issue that does not receive enough attention is how much people rely on intermediaries to access copyrighted works and make fair uses. The entities impacting how people are adapting to online teaching are neither the actual buyers or users of copyrighted materials, nor the authors or copyright holders. The legal and policy debates about the scope of fair use should consider not just the flexibility of the fair use standard but the centrality of intermediaries in facilitating and gatekeeping copyrighted works.

Intermediaries played a role in impacting how individual end users make fair uses even before the pandemic. We have well known examples of intermediaries facilitating fair uses. Google Books is a successful example, making snippets of thousands of books available in a way that courts have described as ‘transformative’. Users from anywhere in the world can search for and view these books. The Internet Archive was making thousands of books available through a practice known as “Controlled Digital Lending” which was more restrictive than the NEL. Universities have been involved in litigation about the scope and extent to which they can make copyrighted chapters available on internal databases. Even before digital technologies, students relied (and still rely in some parts of the world) on copy shops that compile course packs for a fraction of the price of original textbooks.

These examples show us that individual students and educators have heavily relied on intermediaries to make full use of copyright exceptions such as fair use. The realization that intermediaries have a significant role to play in arranging or blocking access to copyrighted works should lead us to question whether pre-pandemic definitions of fair use and public interest were broad enough. Definitions of public interest may have shifted during the pandemic, but it’s time to pay attention to the interests that can be served on regular days and the benefits provided by this increased access. Fair use is inherently flexible and can be adapted to an emergency situation. However, this means we should also be adapting fair use to the changing dynamics of how, when and by whom fair uses are made.

There is another reason we need to pay attention to the role of intermediaries. We are now seeing publishers, large databases and commercial entities creating special programs to provide access during the pandemic. These include flexible licenses, free access for a limited amount of time, and other initiatives to promote access. However, these permission structures are largely based on the discretion of the intermediaries. They often don’t cover all of the books needed and enforce inconsistent limitations.

Accommodations from publishers have led to the creation of a set of rules that are made privately. For example, Macmillan said that it had no objection to teachers reading its books out loud but only if they were doing so on a “non-commercial” basis. HarperCollins laid out its own rules by saying that the videos may only be uploaded to YouTube if they were “unlisted”. This means the videos would not appear on any YouTube pages and individual users would not be able to find them. Scholastic Inc. released a set of guidelines asking teachers to read a disclaimer at the start of the video and to delete the videos by June 30.

This private ordering of what may or may not constitute fair use is in many ways extra-legal and far more restrictive than what fair use would allow. Some have argued that these permissions are not necessary and there is a strong fair use argument for activities such as reading aloud . But these arguments need to take into account the role of digital technologies and platforms in restricting and controlling access to copyrighted works. There is no way for individual teachers to be sure that they are abiding by the law and would probably err on the side of caution, and so intermediaries step in to create more restrictive permission structures than are necessary.

This private ordering also leaves unclear many questions about the scope of fair use in the digital space, what would constitute “non-commercial” and “commercial” use, and how people should use digital platforms to make fair uses. It shouldn’t fall on just intermediaries to make the rules about access, especially during a pandemic.

The pandemic has exposed that we don’t have the tools to take advantage of fair use reliably, whether it’s ‘normal’ circumstances or an emergency. In some ways, we function in a binary system, where we either have commercial paywalls or a flagrant violations of commercial permission structures. Typical mechanisms of getting access to copyrighted works don’t exist right now, so it makes it stark the fact that people often don’t have access except that intermediaries provide it.

Fair use should be responsive to everyday needs — and the role of intermediaries in supporting or frustrating them — too. We have to be wary of not moving too far on the spectrum to copyright maximalism, but also not to the other side and getting rid of permission structures completely.

Here are some recommendations: First, we need to create better ways to educate and empower instructors on more expansive understandings of fair use. Educators worry for myriad reasons like aggressive enforcement by commercial rights holders. We need a more nuanced understanding of how fair use is applied to a combination of online and offline copying, learning and teaching.

Second, some of the existing exceptions and understandings of fair use were made for the physical classroom. Now we not only need to meet the needs of the emergency, but also factor in the use of digital technologies. We need to understand how people use platforms, and intermediaries as central to facilitating and impacting online education.

Third, this moment should prompt us to reflect on the situation for people who lack access to affordable copyrighted works and consistent internet even in non-crisis circumstances. And the role of intermediaries in providing access in normal circumstances. Not everyone has access or devices available at home. People have had to move across time zones and geographies making synchronization difficult, and the use of platforms like YouTube necessary. Lack of affordability of copyrighted works and unreliable internet access should receive more attention in defining the scope of fair use.

Lastly, these flexibilities should continue beyond the emergency to address inequities that have existed prior to the emergency. The pandemic should make us consider why we were not adapting fair use boundaries and public interest to address these inequities before. If we don’t, these inequities will continue to exist. Recognizing individuals’ need to make fair uses is insufficient if we don’t also consider potential enabling and disabling of access by intermediaries. There is an opportunity to collectively realize and acknowledge how fair uses are made and adapt the standard by taking into account the role of intermediaries.