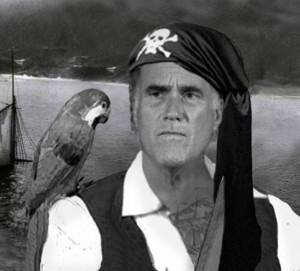

With the election around the corner, polls tied, and a slow news week in the US, it’s time to ask the question that’s on everyone’s mind: could Mitt Romney win with some strategic repositioning on copyright policy? Could the answer be to embrace pirate Romney? Let’s explore.

What do we know about Romney’s views on intellectual property? Really just two things. We know that he joined the roster of anti-SOPA republicans last year when that seemed like the thing to do (“I’m standing for freedom”). And we know that he worries about China stealing our IP. And that’s about it. But it’s more than it seems.

One of the striking things about the SOPA debate was that, when the bill failed, it failed along bipartisan lines. The usual overwhelming bipartisan support for stronger IP enforcement crumbled. For comparison, 2007′s Pro-IP Act–a major expansion of federal responsibility for IP enforcement–passed the House 411-10. In the Senate, approval was unanimous. Similarly, 1998′s Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which established the current take down procedures for infringing content, passed the House by a voice vote (used when not close). Again, in the Senate, approval was unanimous.

So something is going on when such a powerful alignment begins to break apart. We know part of the story is a shift in the balance of lobbying power, as Internet companies begin to throw their weight into policy debates. And part of it is the emergence of an Internet grassroots ready to mobilize against perceived threats. No such counterweight existed in 2007 or 1998, when concerns were raised about those bills.

It’s clear that both developments reflect, in part, a generational shift in attitudes and practices, built around the emergence of the Internet as a primary platform for cultural expression and community. There is clearly a generational politics of the Internet, of which the SOPA fight was arguably the first real test. But is there a partisan politics of intellectual property?

Broadly speaking, at the moment, in the US, the answer is no. Republicans, Democrats, and independents have very similar views on copyright and enforcement–almost always within the margin of error in our survey. With respect to our set of questions about attitudes toward sharing music files, only ‘share with friends’ produced a significant difference, with Democrats leading Republicans 65% to 52%, with Independents at 60%. This is basically the youth effect: young voters tilt democratic, and 76% of 18-29 year olds view sharing with friends as “reasonable” (compared to around 50% of all other groups).* Romney trails Obama in this group by 19%.

(A couple things to note about our charts: these are self-described party affiliations among our 2303 respondents. 24% of this group described itself as Republican; 28% as Democrat; and 37% as Independent. Around 6% chose ‘No preference’ and 3% ‘Refused to answer.” These residual categories generally offered less support for enforcement than the big three.)

What about the two major policy issues of the past year? ISPs, the RIAA, and the MPAA are set to implement a six-strikes model for online copyright infringement, in which customers accused of sharing unauthorized materials via P2P services will receive, first, warnings from their ISPs, then degraded service, and then possibly disconnection and/or a civil suit. The last steps are vaguely defined at present but clearly implied in conversations about the measure.

Let’s step back and ask a more basic question: should people face punishment for “downloading an unauthorized copy of a song or movie?” Among all US adults, the question just barely gets majority support: 51% said yes. Another 7% said it depends on the circumstances–which would be a useful quibble if the law recognized such circumstances. Partisan differences on this question are modest:

- Republicans: 57% said yes; 30% no

- Democrats: 53% yes; 36% no

- Independents: 51% yes; 35% no

This is not strong support for penalties, much less for the powerful criminalization of infringement over the past 15 years. Still, it can claim a majority. But for what?

We asked about the big five penalties at stake in most current and proposed law: warnings, fines, ‘bandwidth throttling,’ disconnection, and jail. Differences in attitudes among the party-identified are small. Warnings and fines are favored by around half of Americans. Limits on Internet speed or functionality attract under 30% support. Disconnection from the Internet is very unpopular at 16%–and falls to 9% if the question specifies household disconnection. Jail time attracts around 10% support.

What about proposals for stronger enforcement by intermediaries, of the kind at the center of the SOPA debate? Because we thought public opinion might be volatile on this issue, we asked a wide variety of questions to tease out differences in language (blocking, filtering, censoring) and differences in the points of application of enforcement (relatively narrow services like Facebook and Dropbox, wider services like Google and ISPs, and the government)

Broadly speaking, Republicans show very slightly more enthusiasm for enforcement than Democrats and very slightly more concern for privacy–with only ISP blocking of pirate sites generating any significant divergence. Again, this is an issue that tracks with age: younger adults are somewhat more tolerant of blocking via services that they can opt out of, and less tolerant of blocking that occurs via major points of access to the Internet in general.

But on the whole, partisan differences are minor. We’d argue that IP policy is still pre-partisan in the US, in the sense that the breakdown of unanimity has not yet been channeled into oppositional stances organized around the two parties. This absence of a partisan politics of the net is often seen as a plus–a virtuous neutrality for those in the netroots–but it also means that the major parties don’t take it seriously enough yet to dispute.

Tensions within the parties on these issues will certainly rise, but by how much? The pressure points for Democrats seem clear, with cultural affinities with (and financial dependence on) the major content industries on the one side, and the divergent attitudes of their young (and, we shall see, minority) base on the other. For Republicans, there is a tempting politics of youth and modernity here, pushing uphill against a rhetoric of property, law and order, and a wider set of demands by big business that have traditionally commanded support. What would partisan uptake of these issues look like? It might look something like the polarization of opinion on abortion in the 1990s, as evangelicals came to power in the Republican party.

Or it might look like what we’re seeing now in Germany and other parts of Europe, with the emergence of small ‘Pirate’ parties as representatives of a nascent environmentalism of the Internet. Our German survey took place before the 9% showing of the Pirate party in Berlin state elections in late 2011 and the subsequent battles over ACTA. Yet the partisan lines around IP politics were already stronger in Europe than in the US, with more consistent defenses of freedom of expression and unimpeded access to the Internet on the left, finding common cause with traditional concerns with privacy on the right. Here is our German data on blocking and filtering by political identification.

Unlike in the US, strong “safe harbor” provisions for web Intermediaries like Google and ISPs have become part of the platforms of the German center-left parties–by all appearances moving ahead of public opinion on these issues. Strong Internet privacy positions have proved popular across the political spectrum, inconveniencing web companies that collect a lot of consumer data (like Google and Facebook) and also provoking conflict with the EU over data retention rules (an important component of strong enforcement).

In France, the left-right divide also incorporates IP enforcement issues, with most Socialists opposing the strong enforcement measures adopted by the conservatives–notably the creation of HADOPI, the Internet enforcement agency.

The UK, for its part, looks more like the US, with the Labour Party playing the lead role in pushing the major recent enforcement bill–the Digital Economy Act–through Parliament in 2009. The landscape is clearly in flux as voters and politicians adapt to a political environment in which Internet politics have begun to matter.

Could Pirate Romney win/have won? Not yet. But we can say with some certainty that the young aren’t getting any younger, and that their attitudes and practices are quite different from those of the policy making generation ahead of them. Among 18-29 year olds, only 37% support penalties for unauthorized downloading. 53% oppose. A better question is: could Pirate Tagg Romney win? Maybe we’ll find out.