The Trans-Pacific Partnership is a sweeping trade agreement, spanning the Pacific Rim, and covering an array of topics, including intellectual property. There has been much analysis of the recently leaked intellectual property chapter of the Trans-Pacific Partnership by WikiLeaks. Julian Assange, WikiLeaks’ Editor-in-Chief, observed “The selective secrecy surrounding the TPP negotiations, which has let in a few cashed-up megacorps but excluded everyone else, reveals a telling fear of public scrutiny. By publishing this text we allow the public to engage in issues that will have such a fundamental impact on their lives.” Critical attention has focused upon the lack of transparency surrounding the agreement, copyright law and the digital economy; patent law, pharmaceutical drugs, and data protection; and the criminal procedures and penalties for trade secrets. The topic of trade mark law and related rights, such as internet domain names and geographical indications, deserves greater analysis.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership is a sweeping trade agreement, spanning the Pacific Rim, and covering an array of topics, including intellectual property. There has been much analysis of the recently leaked intellectual property chapter of the Trans-Pacific Partnership by WikiLeaks. Julian Assange, WikiLeaks’ Editor-in-Chief, observed “The selective secrecy surrounding the TPP negotiations, which has let in a few cashed-up megacorps but excluded everyone else, reveals a telling fear of public scrutiny. By publishing this text we allow the public to engage in issues that will have such a fundamental impact on their lives.” Critical attention has focused upon the lack of transparency surrounding the agreement, copyright law and the digital economy; patent law, pharmaceutical drugs, and data protection; and the criminal procedures and penalties for trade secrets. The topic of trade mark law and related rights, such as internet domain names and geographical indications, deserves greater analysis.

Amongst other things, the latest intellectual property text of the Trans-Pacific Partnership revealed by WikiLeaks reveals a concerted effort to protect the rights and remedies of trade mark owners. The secret agreement is intent upon protecting famous, well known brands. The Trans-Pacific Partnership is a trade deal designed to protect global brands — such as sporting brands like Nike; the information technology trade marks of Apple, Microsoft, IBM, and Google; the logos of Big Food such as McDonalds, and Big Soda, like Pepsi and Coca-Cola.

Much of the discredited Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement has been revived in the trademark provisions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The deal seeks to expand the rights and remedies of trade mark owners to address counterfeiting and domain name cybersquatting. There has also been fierce debate over the relationship between trade mark law and geographical indications. The trade mark sectionsof the Trans-Pacific Partnership lacks sufficient safeguards for the public interest in freedom of speech, cultural criticism, and competition.

In her classic 1999 text, No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies, the Canadian writer Naomi Klein warned of the rise of big brands with the expansion of protection for well-known and famous trade marks. She observed:

Since many of today’s best-known manufacturers no longer produce products and advertise them, but rather buy products and “brand” them, these companies are forever on the prowl for creative new ways to build and strengthen their brand images. Manufacturing products may require drills, furnaces, hammers and the like, but creating a brand calls for a completely different set of tools and materials. It requires an endless parade of brand extensions, continuously renewed imagery for marketing and, most of all, fresh new spaces to disseminate the brand’s idea of itself.

She focused upon the push to expand the reach of brands, with globalisation and the development of international trade agreements. Klein commented that ‘this corporate obsession with brand identity is waging a war on public and individual space: on public institutions such as schools, on youthful identities, on the concept of nationality and on the possibilities for unmarketed space.’

Klein explored the growing opposition among culture jammers to corporate rules. She explained the title of her best-selling book: ‘The book is hinged on a simple hypothesis: that as more people discover the brand-name secrets of the global logo web, their outrage will fuel the next big political movement, a vast wave of opposition squarely targeting transnational corporations, particularly those with very high name-brand recognition’. Klein charted the counter-attacks by culture-jammers, Adbusters, and the fair trade movement such trade marks. In the Tenth edition of the book, Klein reflected that the techniques of branding had thrived and adapted.

In retrospect, No Logo is prophetic about the corporate efforts to expand the protection in respect of trade mark law, and the associated rights and remedies, particularly through international trade agreements — such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

By and large, there is significant consensus in respect of the trade mark provisions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

In the 2014 Special 301 report, the United States Trade Representative discussed its vision in respect of trade mark law:

Trademarks help consumers distinguish a company’s products and services from competing products and services, and thereby serve a critical source identification role. The goodwill represented in a company’s trademarks is often one of the company’s most valuable business assets. However, in numerous countries legal and procedural obstacles exist to securing and enforcing trademark rights. Additionally, many countries lack transparency and consistency in administrative registration procedures. In other countries, governments often do not provide the full range of internationally-recognized trademark protections. For example, dozens of countries do not offer a certification mark system for use by foreign or domestic industries. The lack of a certification mark system can make it more difficult to secure protection for products with a quality or characteristic that consumers associate with the product’s geographic origin.

The United States Government has been keen to address perceived legal and procedural obstacles to enforcing trade mark rights in the Pacific Rim.

The International Trademark Association (INTA) has lobbied strongly for an expansion of trade mark rights in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. INTA has emphasized that ‘TPP participants should join the Singapore Treaty on the Law of Trademarks and the Madrid Protocol.’ Moreover, INTA has maintained that ‘The TPP Agreement should extract and emphasize the key components of these treaties, namely.’ The International Trademark Association (INTA) has also demanded that the Trans-Pacific Partnership address provide ‘statutory protection for well-known marks and dilution protection for famous marks.’

The Trans-Pacific Partnership text highlights divisions over the types of signs registrable as trademarks. Article QQ.C.1 provides ‘No Party may require, as a condition of registration, that a sign be visually perceptible, nor may a Party deny registration of a trademark solely on the ground that the sign of which it is composed is a sound.’ However, Vietnam, Brunei, Canada and Japan oppose the inclusion of scent as a non-traditional sign to be protected under trade mark law. The countriesa greed that ‘A Party may require a concise and accurate description, or graphical representation, or both, as applicable, of the trademark.’

Article QQ.C.2 deals with collective and certification marks. Article QQ.C.3 addresses the use of identical or similar signs. There was significant argument and disagreement between the parties as to the relationship between trade mark law and geographical indications in these clauses.

Article QQ.C.4 provides that ‘Each Party may provide limited exceptions to the rights conferred by a trademark, such as fair use of descriptive terms, provided that such exceptions take account of the legitimate interest of the owner of the trademark and of third parties.’ The Electronic Frontier Foundation has highlighted a number of instances of abuse of trade mark rights to suppress political speech and cultural criticism. In a recent dispute, the civil society organisation has insisted that trade mark rights should not trump free speech. Famously, the Electronic Frontier Foundation defended The Yes Men against an intellectual property law suit by the United States Chamber of Commerce:

The Yes Men vs The US Chamber of Commerce http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=flsNwClU1dI

The United States has sought to provide protection for the public interest under trade mark law, through a liberal application of the First Amendment, and the use of the doctrine of fair use in respect of trade mark dilution. There should be scope for broad exceptions under trade mark law in the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Article QQ.C.5 provides for the protection of well-known trade marks. The clause stresses: ‘No Party may require as a condition for determining that a trademark is well-known that the trademark has been registered in the Party or in another jurisdiction, included on a list of well-known trademarks, or given prior recognition as a well-known trademark.’ The Article provides:

‘Article 6bis of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (1967) shall apply, mutatis mutandis, to goods or services that are not identical or similar to those identified by a well-known trademark, whether registered or not, provided that use of that trademark in relation to those goods or services would indicate a connection between those goods or services and the owner of the trademark, and provided that the interests of the owner of the trademark are likely to be damaged by such use.’

The Article notes: ‘Each Party recognizes the importance of the Joint Recommendation Concerning Provisions on the Protection of Well-Known Marks (1999) as adopted by the Assembly of the Paris Union for the Protection of Industrial Property and the General Assembly of WIPO.’ The Article emphasizes: ‘Each Party shall provide for appropriate measures to refuse the application or cancel the registration and prohibit the use of a trademark that is identical or similar to a well-known trademark,28 for identical or similar goods or services, if the use of that trademark is likely to cause confusion with the prior well known trademark.’ Moreover, A Party may also provide such measures inter alia in cases in which the subsequent trademark: is likely to deceive or risk associating the trademark with the owner of the well-known trademark, or constitutes unfair exploitation of the reputation of the well-known trademark.’

Article QQ.C.6 deals with the examination and registration of trademarks. Article QQ.C.7 focuses upon the provision of an electronic trademarks system. Article QQ.C.8 provides that ‘Each Party shall adopt or maintain a trademark classification system that is consistent with the Nice Agreement Concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks (Nice Classification) of June 15, 1957, as revised and amended.’ Article QQ.C.9 stipulates that ‘each Party shall provide that initial registration and each renewal of registration of a trademark shall be for a term of no less than 10 years.’

Article QQ.C.10: provides: ‘No Party may require recordal of trademark licenses: to establish the validity of the license; as a condition for any right that a licensee may have under that Party’s law to join infringement proceedings initiated by the holder, or to obtain by way of civil infringement proceedings damages resulting from an infringement of the trademark which is subject to the license]; or as a condition for use of a trademark by a licensee, to be deemed to constitute use by the holder in proceedings relating to the acquisition, maintenance and enforcement of trademarks].’ Vietnam, Mexico, Chile, Brunei, and Malaysia have opposed a large part of this text.

Louis Vuitton, Wikimedia

The United States Trade Representative has been deeply disturbed by the perceived problem of trademark counterfeiting. In the 2014 Special 301 report, the United States Trade Representative commented:

The problems of trademark counterfeiting and copyright piracy continue on a global scale and involve mass production and sales of a vast array of fake goods, including counterfeit semiconductors, medicines, health care products, food and beverages, automobile parts, such as air bags, aircraft parts, apparel and footwear, toothpaste, toys, shampoos, razors, electronics, batteries, chemicals, sporting goods, motion pictures, and music.

Consumers, legitimate producers, and governments are harmed by rampant trademarkcounterfeiting and copyright piracy. Consumers may be harmed by fraudulent and potentially dangerous counterfeit products, including medicines, auto and airplane parts, and semiconductors. Producers face the risk of diminished profits and loss of reputation when consumers purchase fake products, and governments may lose tax revenue and find it more difficult to attract investment. Infringers generally pay no taxes or duties, and often disregard basic standards for worker health and safety and product quality and performance.

(The United States Trade Representative’s conflation of trademark counterfeiting and copyright piracy is quite confusing — given that they are different disciplines in intellectual property, and not necessarily analogous). The United States said that it ‘continues to urge trading partners to undertake more effective criminal and border enforcement to stop the manufacture, import, export, transit, and distribution of pirated and counterfeit goods.’ The United States Trade Representative emphasized that it ‘engages extensively with its trading partners through bilateral consultations, trade agreements, and international organizations, to ensure that penalties are deterrent, and include significant monetary fines and meaningful sentences of imprisonment.’

The Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement 2012 contained a number of measures designed to address trade mark counterfeiting. There was uproar amongst civil society groups in the European Union, North America, Australia, and New Zealand about the proposed agreement. After much criticism from the European Parliament, and the Australian Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement 2012 collapsed.

The Zombie Agreement has refused to die; and has been reanimated in new forms in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The International Trademark Association (INTA) has also demanded that the Trans-Pacific Partnership address ‘enhancing protection against counterfeiting (tougher penalties; simplified damages calculation; landlord liability; online sales)’, ‘Providing for seizure of goods in transit’; and ‘Offering trademark owners greater access to information about counterfeiters that is held by customs and other agencies.’

The Trans-Pacific Partnership features a number of clauses on trademark counterfeiting. Article QQ.H.4 deals with civil procedures and remedies. The article states: ‘Each Party shall provide that in civil judicial proceedings its judicial authorities have at least the infringer to pay the right holder damages adequate to compensate for the injury the right holder has suffered because of an infringement of that person’s intellectual property right by an infringer who knowingly, or with reasonable grounds to know, engaged in infringing activity.’ The article provides: ‘At least in cases of copyright or related rights infringement and trademark counterfeiting, each Party shall provide that, in civil judicial proceedings, its judicial authorities have the authority to order the infringer, at least as described in paragraph 2, to pay the right holder the infringer’s profits that are attributable to the infringement.’ The article also proposes: ‘In civil judicial proceedings, with respect to trademark counterfeiting, each Party [US propose: shall] [NZ/JP/MX/AU/BN/MY propose: may] also establish or maintain a system that provides for one or more of the following: pre-established damages, which shall be available upon the election of the right holder; or additional damages.’

Article QQ.H.5 deals with provisional measures, including seizure: ‘In civil judicial proceedings concerning copyright or related rights infringement and trademark counterfeiting, each Party shall provide that its judicial authorities shall have the authority to order the seizure or other taking into custody of suspected infringing goods, material and implements relevant to the infringement, and, at least for trademark counterfeiting, documentary evidence relevant to the infringement.’

In Article QQ.H.6, there are extensive special requirements related to border measures and customs measures.

Article QQ.H.7 addresses criminal procedures and remedies for trademark counterfeiting and copyright piracy: ‘Each Party shall provide for criminal procedures and penalties to be applied at least in cases of willful trademark counterfeiting or copyright or related rights piracy on a commercial scale.’

There has also been concern about how trade mark law has been applied in respect of intermediaries such as eBay.

Given the controversy over the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement 2012, it is disturbing that similar measures are pushed forward in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Notably, the United States Trade Representative has failed to ameliorate the harsh proposals, with safeguards and protections for privacy, free speech, fair use, and competition. As James Love has noted, ‘While pushing for radical expansions of the global standards for intellectual property rights, Ambassador Froman is also trying to narrow or eliminate the safeguards found in other intellectual property right agreements.’

4. Internet Domain Names and Cybersquatting

[ICANN domains protected by Stormtroopers Image Credit: veni markovski/Flickr]

In the 2014 Special 301 report, the United States Trade Representative discussed its vision in respect of trade mark law: and Internet Domain Names:

Another area of concern for trademark holders is the protection of their trademarks against unauthorized uses under top level domain extensions. U.S. rights holders face significant trademark infringement and loss of valuable Internet traffic because of such uses. A related and growing concern is that certain country code top level domain names (ccTLD) lack transparent and predictable uniform domain name dispute resolution policies (UDRPs). Effective UDRPs should assist in the quick and efficient resolution of these disputes. The United States encourages its trading partners to provide procedures that allow for the protection of trademarks used in domain names, and to ensure that dispute resolution procedures are available to prevent the misuse of trademarks.

To this end, the United States Trade Representative has been lobbying for the text on the topic in the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership also puts forward text on domain name cybersquatting — even though there is already domestic laws addressing such issues (such as the Clinton era laws on cybersquatting), and the international arbitration system for domain names.

In respect of the previous leaked text, Susan Chalmers has made the point that there will be a conflict of regimes in respect of Internet Domain Names: ‘Subjugating a ccTLD to a plurilateral trade agreement is problematic’. She observed: ‘As a matter of principle, ccTLDs should decide themselves what their policies are and have the flexibility to determine how and when those policies should be modified, in a regulatory environment marked by fluidity that allows individual ccTLDs to respond best to the needs of their particular community.’ Susan Chalmers fears: ‘The ccTLD’s policy development autonomy could be lost as it is directed, through legislation or otherwise, to revise its policies into harmony with the TPP.’

Article QQ.C.12 of the new leaked text of the Trans-Pacific Partnership addresses the topic of domain name squatting thus:

In connection with each Party’s system for the management of its country-code top-level domain (ccTLD) domain names, the following shall be available:

(a) an appropriate procedure for the settlement of disputes, based on, or modeled along the same lines as, the principles established in the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy, or that is: (i) designed to resolve disputes expeditiously and at low cost, (ii) fair and equitable, (iii) not overly burdensome, and (iv) does not preclude resort to court litigation; and

(b) online public access to a reliable and accurate database of contact information concerning domain-name registrants;

(c) in accordance with each Party’s laws and, or relevant administrator policies regarding protection of privacy and personal data.

Article Q.C.12 (2) provides: ‘In connection with each Party’s system for the management of ccTLD domain names, appropriate remedies, shall be available, at least in cases where a person registers or holds, with a bad faith intent to profit, a domain name that is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark.’

It is noticeable that there is little way of text on public interest safeguards in respect of internet domain names. In her book, Internet Domain Names, Trade Marks and Free Speech, Professor Jacqueline Lipton has commented that there is too much focus upon the private interests of trademark holders in respect of Internet Domain Names. She maintains: ‘Since the adoption of the trademark-focused UDRP, very little has been done in the way of global policy development to protect other interests in domain names.’ Lipton observed that ‘such interests might include free speech, privacy, personality rights, and rights in geographic and cultural indicators.’ She even worries that ‘competing commercial interests are not currently addressed particularly effectively under the UDRP.’

The Trans-Pacific Partnership also has extensive text on geographical indications.

The International Trademark Association (INTA) has argued that ‘Provisions dealing with the relationship between trademarks and GIs should be included in the TPP Agreement, particularly.’

There is basic agreement that ‘The Parties recognize that geographical indications may be protected through a trademark or sui generis system or other legal means.’

A number of countries — notably Chile — have pushed for stronger protection of geographical indications for wine regions. In addition, Chile has also proposed that ‘The Parties recognize the geographical indication Pisco for the exclusive use for products from Chile and Peru.’ This proposal has been widely condemned by other countries. Chile, Singapore, Brunei, and Mexico have proposed an annex, which lists protected geographical indications. The United States has led the opposition to such a proposal.

The United States has sought to nobble these proposals on geographical indications. In its Special 301 Report, the United States explains its antipathy to geographical indications:

The United States is working intensively through bilateral and multilateral channels to advance U.S. market access interests and to ensure that the trade initiatives of other countries, including with respect to geographical indications (GIs), do not undercut U.S. industries’ market access. GIs typically consist of place names (or words associated with a place) and they identify products or services as having a particular quality, reputation, or other characteristic attributable to their geographic origin.

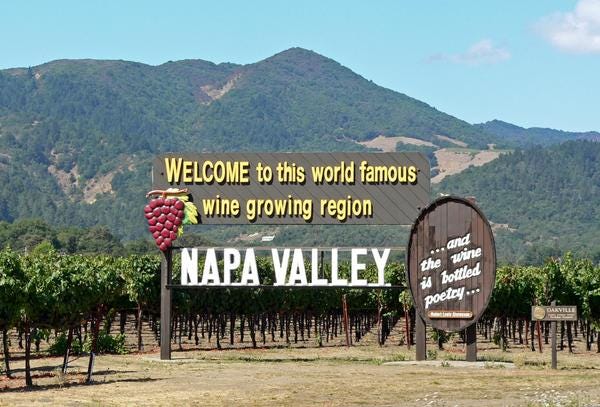

The United States much prefers to rely upon trade mark protection (even though certain regions in the United States, such as the Napa Valley and Sonoma, are renowned for wine.

The European Union has been watching the debate over geographical indications in the Trans-Pacific Partnership closely. The European Union is at loggerheads with the United States over the protection of geographical indications in the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.

In the conclusion to her groundbreaking book, No Logo, Naomi Klein called for a coalition of activists to challenge the hegemony of Big Brands, and reclaim the cultural commons: ‘Ethical shareholders, culture jammers, street reclaimers, McUnion organizers, human-rights hactivists, school-logo fighters and Internet corporate watchdogs are at the early stages of demanding a citizen-centered alternative to the international rule of brands.’ She suggested: ‘That demand, still sometimes in some areas of the world whispered for fear of a jinx, is to build a resistance — both high-tech and grassroots, both focused and fragmented — that is as global, as capable of coordinated action, as the multinational corporations it seeks to subvert.’ Such a challenge remains with international trade agreements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, with its panopoly of rights and remedies for global trade marks and big brands. There will need to be a strong coalition of civil society groups from around the Pacific Rim to stop the fast-tracking of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Dr Matthew Rimmer is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow, working on Intellectual Property and Climate Change. He is an associate professor at the ANU College of Law, and an associate director of the Australian Centre for Intellectual Property in Agriculture (ACIPA). He holds a BA (Hons) and a University Medal in literature, and a LLB (Hons) from the Australian National University, and a PhD (Law) from the University of New South Wales. He is a member of the ANU Climate Change Institute. Dr Rimmer is the author of Digital Copyright and the Consumer Revolution: Hands off my iPod, Intellectual Property and Biotechnology: Biological Inventions, and Intellectual Property and Climate Change: Inventing Clean Technologies. He is an editor of Patent Law and Biological Inventions, Incentives for Global Public Health: Patent Law and Access to Essential Medicines, and Intellectual Property and Emerging Technologies: The New Biology. Rimmer has published widely on copyright law and information technology, patent law and biotechnology, access to medicines, clean technologies, and traditional knowledge. His work is archived at SSRN Abstracts and Bepress Selected Works.