[Cross posted from EIFL.org, Link (CC-BY)] For the last few decades, the United States has been aggressively and systematically “exporting” half of its copyright system. In treaties and in trade agreements, the US has insisted on longer terms of protection, stiffer penalties for infringement, legal protection for digital locks, and a variety of other measures designed to benefit copyright holders. Only recently, however, has the US even acknowledged the part of its copyright law that protects the public, including schools, libraries, technologists, and entrepreneurs, against overreaching copyright laws.

[Cross posted from EIFL.org, Link (CC-BY)] For the last few decades, the United States has been aggressively and systematically “exporting” half of its copyright system. In treaties and in trade agreements, the US has insisted on longer terms of protection, stiffer penalties for infringement, legal protection for digital locks, and a variety of other measures designed to benefit copyright holders. Only recently, however, has the US even acknowledged the part of its copyright law that protects the public, including schools, libraries, technologists, and entrepreneurs, against overreaching copyright laws.

We in the US have known all along, however, that the real secret of the US’s relative success in both the culture and technology spheres is the balance to copyright protections provided by limitations and exceptions, especially the fair use doctrine.

Fair use is a big deal

The fair use doctrine is an open-ended limitation to the exclusive rights granted to copyright holders, designed to allow free use for socially valuable purposes such as criticism, commentary, teaching, and news reporting. It has existed in the US for over a century as judge-made law, but was codified in the 1976 Copyright Act at Section 107. While critics of the doctrine sometimes mischaracterize it as a “mere” affirmative defence or excused infringement, the Copyright Act itself refers to “the right of fair use”, and the US Supreme Court has said that fair use is part of the “traditional contours” of copyright and one of the law’s “built-in First Amendment safety valves.” Fair use, in other words, is a big deal in the US.

If we really want to encourage the development of a thriving global culture, then open norms such as fair use should become as widespread as measures of copyright enforcement. The benefits of open norms are equally useful to all, and there is no reason why other countries and legal systems can’t take advantage of the flexibility that open norms like fair use provide. Here I survey some of the key benefits of open norms, and explain why there is nothing inherent about open norms that precludes their adoption in the copyright law of any legal system.

Copyright keeps up with technology

Grand Study Hall, New York Public Library. The library was an early partner in the Google Books scanning programme. A unanimous decision by a US federal circuit court in October 2015 strongly affirms fair use. Photo credit Alex Proimos, Sydney, Australia.A key benefit of open norms is that they ensure that the law keeps pace with technology. In the US, the fair use doctrine has been pivotal in encouraging the development of new technologies that have become central to contemporary life: the personal computer, the search engine, and the VCR have all benefited from reasoned application of the doctrine at key points in their development. Where some countries have struggled to overhaul their copyright laws to make them “fit for purpose” in the Internet age, US courts have been able to use fair use to bless important new technologies without the need for legislative revision.

Grand Study Hall, New York Public Library. The library was an early partner in the Google Books scanning programme. A unanimous decision by a US federal circuit court in October 2015 strongly affirms fair use. Photo credit Alex Proimos, Sydney, Australia.A key benefit of open norms is that they ensure that the law keeps pace with technology. In the US, the fair use doctrine has been pivotal in encouraging the development of new technologies that have become central to contemporary life: the personal computer, the search engine, and the VCR have all benefited from reasoned application of the doctrine at key points in their development. Where some countries have struggled to overhaul their copyright laws to make them “fit for purpose” in the Internet age, US courts have been able to use fair use to bless important new technologies without the need for legislative revision.

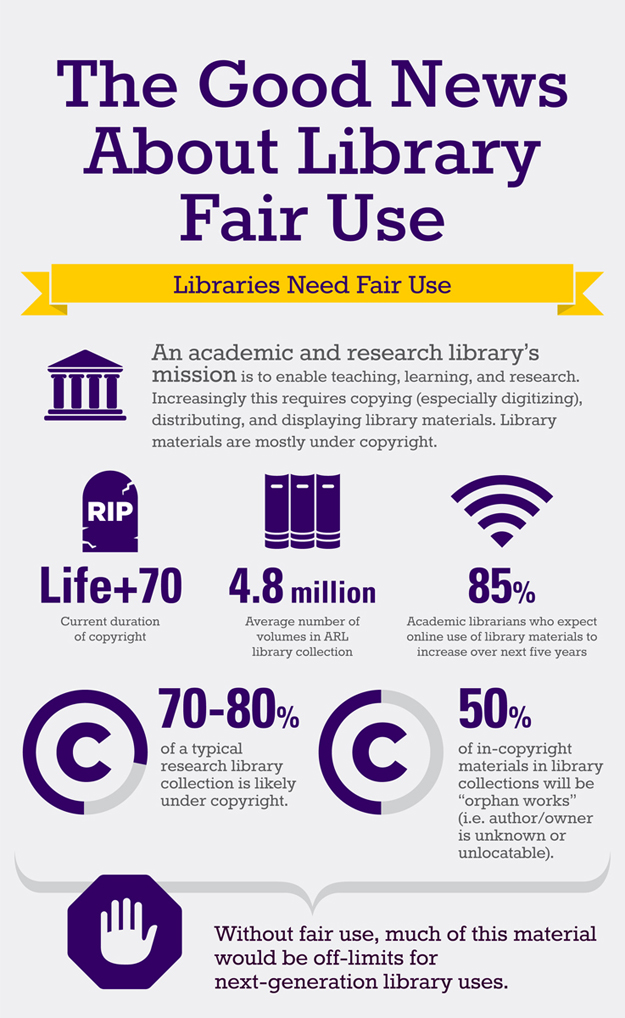

Enables digital library projects

The adaptability of open norms is a significant benefit over specific exceptions for two key reasons. First, developing consensus legislation can take many years, a delay that the public shouldn’t have to endure. Second, and more importantly, technology has often moved on by the time consensus on legislation emerges. The history of copyright exceptions in the US is replete with ad hoc adaptations that were useless as soon as they were signed into law because they were tailored too closely to technological practice that was already outmoded. For example, the specific exception for libraries has languished for over a decade in a perennial state of half-baked legislative revision; in the meantime it is fair use that has allowed important new library projects involving digitization for search, text-mining, preservation, and accessible formats to go forward.

Open norms also allow more generally for flexible and reasonable adaptation to changing circumstances. The US has a full slate of specific limitations and exceptions that take up the vast majority of the first chapter of our Copyright Act. For example, a library can make up to three copies of unpublished materials in its collection for purposes of preservation, and an elementary school teacher can screen a film in her classroom without paying for permission. And yet the scope of these exceptions can often fall short of what is needed to serve the intended goal. After all, when an exception is being developed, the legislator cannot be expected to anticipate every use to which the exception might be put.

In addition, specific exceptions tend to embody negotiated deals that represent the priorities and values of a few stakeholders at a given time, and they don’t always stand the test of time. The library provisions in US law, for example, place hard numerical limits on how many copies may be made for preservation or replacement of damaged works. Those numbers reflect practices that were common for works copied in microfiche format. They no longer make sense in the digital environment nor are they in keeping with library best practices today. Therefore US libraries today routinely rely on fair use to permit preservation activities beyond those described in the specific provision.

Common sense approach to snippets

Snippets from a Google Books searchAn example of the way a narrow specific exception can have untoward adverse consequences in the digital age is the recent decision by the Chamber for Copyright Arbitration of the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (DPMA) regarding the use of “snippets” in search engine results. Interpreting a German law that allows the use of only “single words” and “very small text fragments” without permission, the DPMA ruled that search engine results of more than seven words would exceed “very small fragments” and therefore require payment. Why seven words are permissible but eight words are too many is left as an exercise for the reader.

Snippets from a Google Books searchAn example of the way a narrow specific exception can have untoward adverse consequences in the digital age is the recent decision by the Chamber for Copyright Arbitration of the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (DPMA) regarding the use of “snippets” in search engine results. Interpreting a German law that allows the use of only “single words” and “very small text fragments” without permission, the DPMA ruled that search engine results of more than seven words would exceed “very small fragments” and therefore require payment. Why seven words are permissible but eight words are too many is left as an exercise for the reader.

Compare this outcome to the recent decision in the Google Books case in the US, where fair use was applied to permit display of “snippets” of varying sizes so long as they are clearly designed to allow the researcher to determine whether the result was truly relevant, and do not threaten to substantially harm the market for the original work.

Are open norms incompatible with civil law systems?

Despite the benefits of open norms, some argue that countries with civil law systems (and other non-US countries) are not suited to implement open norms. I believe this view is largely a result of the historical accident that fair use developed in the US as a common law, judge-made doctrine for over a century before it was codified in the text of the statute in 1976. This common law origin has given fair use a reputation as “judge-made”, and therefore uncertain, that seems alien to practitioners in civil law countries.

In reality, the application of law to facts is hardly unique to the common law tradition, nor does it necessarily create uncertainty. Similarly, the use of prior decisions in the same or other jurisdictions as guidance for application of the law is not unique to countries that recognize precedent.

Civil law judges routinely apply relatively abstract standards to the facts before them, determining whether a party engaged in unfair competition or acted negligently, for example. It is also well-documented that while civil law judges may not be bound by prior opinions in the way that common law judges are, they increasingly consult the opinions of other courts for advice on proper application of the law.

It is especially bizarre to suggest that judges in civil law countries cannot apply open norms considering that the copyright laws in many such countries currently allow their courts to apply a specific exception in a specific case only if the second and third steps of the Berne Convention three-step-test are met. That is, the court may permit the use only if it determines that the use does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the rights holder. These steps are at least as abstract and difficult to apply as concepts of fair use or fair dealing.

“No vehicles in the park”

More generally, any lawyer can tell you that virtually any law is capable of a multitude of interpretations and applications to specific circumstances. (It’s the subject of a famous debate in the US regarding the allegedly clear meaning of the phrase “No vehicles in the park.”) Judges in any legal system will have to exercise some, well, judgment in considering how best to apply the words of a statute to specific facts. There will always be a core of fairly predictable, stable applications of the law and a margin or periphery of harder cases. Copyright is no exception.

Marvin Gaye and the idea-expression distinction

![Source: Wikipedia. The original uploader was Qit16 at German Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.eifl.net/sites/default/files/robin_thicke_blurred_lines_cover.png) Source: Wikipedia. The original uploader was Qit16 at German Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia CommonsTo give an example, any copyright system must recognize what is known as the “idea-expression distinction” whereby copyright protects a particular expression of an idea, but not the idea itself.

Source: Wikipedia. The original uploader was Qit16 at German Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia CommonsTo give an example, any copyright system must recognize what is known as the “idea-expression distinction” whereby copyright protects a particular expression of an idea, but not the idea itself.

This is because, in any country, copyright protects a particular expression of an idea, but not the idea itself. So, the author of a play that involves star-crossed lovers from feuding families does not thereby acquire rights in that idea, nor does she need to fear that some other playwright will come out of the woodwork and demand a licence for use of the idea. On the other hand, an infringer cannot evade the law by merely changing the names of the main characters, or making other trivial alterations, while keeping the expression in the work intact. Copyright protects the owner against more than literal copying, but does not grant property in general ideas. Where does one draw the line between idea and expression?

In the US there is a famous opinion by the aptly named Judge Learned Hand, who says of the line between free idea and protected expression, “Nobody has ever been able to fix that boundary, and nobody ever can.” The line will be different for different art forms, and perhaps even for different genres or works. It is a quintessentially case-by-case determination, and it must be made by any court in any country applying a copyright statute to an alleged infringement, whatever the legal system.

The recent high-profile lawsuit brought by the heirs of Marvin Gaye against the contemporary pop stars Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke is an example of the difficulty in making this distinction. The Thicke/Pharrell song “Blurred Lines” does seem to bear a certain resemblance to Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up,” but is the resemblance due to shared musical ideas (a sparse arrangement with party sounds, a cowbell, a falsetto vocal) which are unprotected, or did “Blurred Lines” copy protected expression, with only trivial alterations?

While many experts (including me!) disagree with the court’s decision that Thicke and Pharrell copied protectable expression from Gaye’s 1970s composition, they (we!) have to admit the outcome is not indefensible. The court was applying a highly abstract, context sensitive distinction that is inherent to any copyright system.

So, if judges in civil law countries are competent to decide, on a case-by-case basis, whether a given work has crossed this ineffable (or even blurred!) line between idea and expression, they are certainly competent to apply, similarly, an open norm like fair use.

Other concerns about the adoption of open norms in civil law countries are even less resilient when scrutinized.

Millions of people rely on fair use

Do open norms, like fair use, spawn expensive litigation (due in part to their supposed uncertainty)? No. In reality, any US lawyer can tell you that the number of lawsuits about fair use is no more than in any other area of US law. (I confess, we are a bit more litigious around here but that’s got nothing to do with fair use!). Indeed, the vast majority of copyright litigation in the US concerns online file-sharing, a practice that is completely unrelated to fair use.

Millions of ordinary Americans rely on fair use everyday to do things like time-shift television or forward emails. Libraries rely on fair use for digitization and support for teaching. Million dollar corporations rely on it to protect core business functions, including parody, reverse engineering, and news reporting. There is no concern that the doctrine is somehow too uncertain to permit these activities.

While new technologies and cultural practices, such as search engines or appropriation art, may draw high-profile challenges when they first emerge, confidence follows fairly quickly as the courts demonstrate clearly how fair use should apply.

An ordered system

Is fair use too uncertain because in some high profile cases the outcomes have reversed at each stage of review? No. In a few well-known cases, the district court ruled one way, the appellate court reversed, and the Supreme Court reversed again—because these were hard cases.

Of course, this doesn’t prove anything. Hard cases come along in every area of the law, and only the hardest cases (where the loser nevertheless reasonably believes they have a chance of winning on appeal) are litigated all the way to the US Supreme Court. The vast majority of fair uses are never litigated, and the few that are have been decided quickly or settled out-of-court before a decision can be rendered. They are, in other words, easy cases!

The courts’ treatment of cases at the margins, where difficult cutting edge issues are resolved, is not indicative of whether the law is useful to the vast majority of people who are working at its core. The key question is whether the law is working in the majority of cases, especially after difficult cases help to settle disputes at the margins. Several US academics have shown that courts are applying fair use in a coherent way that reveals core principles, patterns, and clusters, not chaos.

Cases involving libraries and fair use are encouraging

The relative certainty and stability of fair use as applied to libraries can be seen in the string of opinions in the HathiTrust and Google Books cases. While these may seem like controversial, cutting-edge cases because they involve the digitization of millions of in-copyright books (and the authors and publishers were certainly quite upset about it), copyright experts were mostly united in thinking that these cases should be fairly straightforward fair uses.

We have already seen a long line of cases dealing with the realm of digital search online, and the logic of these cases seemed to apply clearly to the HathiTrust and Google Books digitization efforts.

In HathiTrust, the court blessed mass digitization of in-copyright books for search, text-mining, preservation, and access for people with print disabilities. In the Google Books case that was finally decided on 16 October 2015, six judges – two district court judges and four appellate judges sitting on two different panels – all concluded for substantially the same reasons that both the libraries and Google had engaged in fair use. The Authors Guild has threatened to appeal the latest opinion to the Supreme Court, but experts doubt the Court will agree to hear the case.

Another recent case, AIME v. UCLA, dealt with library copying and streaming video from DVDs to college students online.

Although the case was ultimately decided on other grounds, it included a favorable discussion of how fair use would apply to digital streaming, which gives libraries substantial comfort in applying the doctrine in such circumstances.

The utility of fair use for libraries and other cultural institutions is also shown, in part, by the relative paucity of lawsuits taken against libraries and the results of the cases that are quite encouraging. It is simply not a wise bet to sue a library when it makes a conscientious application of fair use.

Fair use can benefit rightsholders

Another interesting case, did not involve a library as a party but applied fair use to the very library-like activities of a private database publisher. In White v. West, West had digitized and made available thousands of legal briefs to support legal research. The court found that by adding metadata and other information and by making the the legal briefs searchable, West had added substantial value. The court also found that support for legal research was not one of the authors’ original intended uses of the briefs, so there was no harm to the authors’ core market.

The court therefore found that making these opinions available in support of research was a fair use. Libraries interested in digitizing primary materials of this kind in support of research can take inspiration from the facts and reasoning in this case. The case also shows how rightsholders (West is a major publisher) can also benefit from fair use.

Everyone should enjoy the benefits of an open norm

In conclusion, I believe rather strongly that there’s nothing special about the US that entitles us to a monopoly on open norms, nor do I want to keep others from enjoying its benefits. Indeed, there are already over forty countries around the world from every kind of legal system that have adopted flexible limitations in their copyright law. Open norms ensure balance and flexibility in any legal system.

Brandon Butler is Practitioner-in-Residence at the Intellectual Property Law Clinic at the American University Washington College of Law (WCL). Before joining WCL, Prof Butler was the Director of Public Policy Initiatives at the Association of Research Libraries (ARL), where he worked on the ARL Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries (2012).

For information concerning EIFL partner countries, see Time to consider open norms (seriously).