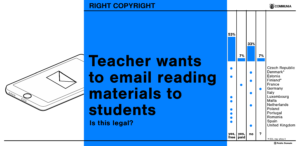

[Teresa Nobre, Communia Association, Link, (CC-0)] Today we publish the findings of a new study carried out by Teresa Nobre that intends to demonstrate the impact exerted by narrow educational exceptions in everyday practices. She accomplishes this purpose by analysing 15 educational scenarios involving the use of protected materials under the copyright laws of 15 European countries: the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom.

[Teresa Nobre, Communia Association, Link, (CC-0)] Today we publish the findings of a new study carried out by Teresa Nobre that intends to demonstrate the impact exerted by narrow educational exceptions in everyday practices. She accomplishes this purpose by analysing 15 educational scenarios involving the use of protected materials under the copyright laws of 15 European countries: the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom.

Almost no case law was analysed, and uses permitted under licenses, namely extended collective licenses, are not indicated here. Thus, the study does not give a detailed picture of all the countries under analysis.

Materials available for educational uses

This study confirms what we have known for a long time: that not all copyrighted works are treated equally in the context of education. Some educational exceptions exclude the use of certain types of works (textbooks and academic books in France and Germany, dramatic works and cinematographic works in Denmark and Finland and musical scores in France and Spain). Other laws contain restrictions in relation to the extent or degree to which a work can be used for educational purposes, thus creating obstacles to the use of entire works, namely short works (e.g. individual articles, short videos and short poems) and images (e.g. artworks, photographs and other visual works).

The Commission’s proposal covers all types of works and allows them to be used to the necessary extent. However, Member States can decide that licenses take precedence, generally or in relation to some types of works. This means that, unless the proposal is amended, materials available for educational use will continue to be subject to different rules and licenses in some Member States.

Traditional vs Modern Educational Practices

While the proposal of the Commission only focuses on digitally supported education, the problems and legal uncertainty that the education community faces go beyond the digital and online environments. For instance, extent restrictions in France, Luxembourg, Portugal and Spain, and the exclusion of certain types of works from the scope of the exception in Denmark, Finland, France and Spain prevent the performance in class of an entire piece of music and/or a dramatic work and/or the screening of an entire film.

Treating educational activities differently based on the rights or technologies involved adds complexity to an already complex legal framework. For example, in Italy and in the Netherlands performances made in the context of education are excluded from the scope of protection of the public performance right. This means that a teacher can screen a film from a DVD without having to worry about copyright. However, if the same teacher wants to show a film from the Youtube, she probably cannot do it, because a different right – the public communication right – is triggered.

Even in the context of digital uses, the Commission proposal falls short of the expectations. For instance, when it comes to sharing resources through online platforms, several of the countries curtail the potential beneficiaries of these types of uses, but only Spain and the United Kingdom expressly require such use to be made through a closed/secure electronic network, accessible only by students and teachers from a given educational establishment, as foreseen in the Commission’s proposal. Moreover, most of the countries under analysis allow sharing educational materials via email, the cloud, etc.

Non-Formal Education

The majority of the countries under analysis does not discriminate against the person or entity running the educational activity, focusing solely on the educational purpose of the use. However, a significant number of these countries only allows educational uses if they are made by schools or other formal educational establishments. These are Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom. In these countries, museums, libraries and other providers of non-commercial education must therefore ask for permission before making certain uses of protected materials in their educational programes.

Conclusion

The landscape of educational exceptions in Europe is fragmented due to four main obstacles: act of use, type of user, type of work and extension of work.

While the European Commission does not restrict the types of works or other subject matter that can be used under the proposed exception for digital and cross-border teaching activities or the extent to which those works can be used, the proposed exception only covers certain acts of use and limits the type of users that can benefit from the exception. Indeed, its proposal focuses solely on digitally supported education for the benefit of a closed list of persons providing or receiving education in educational establishments.

These scenarios show that, unless the Commission’s proposal is substantially amended, several European countries will be stuck with narrow copyright exceptions that will continue to curtail educational practices at various levels.

Further reference

The study is part of our RIGHT COPYRIGHT campaign. If you have not done so, we encourage you to go to the campaign website and sign the petition to ask for a better copyright reform for education.