Comments to the International Trade Commission, re: USMCA

Docket # ITC-2018-0375

Michael Palmedo

American University Washington College of Law

Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property

I work for the Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property (PIJIP) at the American University Washington College of Law. We have an interdisciplinary project that studies the economic effects of legal provisions in copyright laws, specifically copyright limitations that are relied upon by various firms in the information and research sectors. I manage the economic side of this research, and Professor Sean Flynn manages the legal side of it. The project is partially funded by Google. Thank you for the opportunity to present my views on USMCA.

Our research indicates that American firms operating overseas in industries that rely on copyright exceptions enjoy better outcomes on average when our trading partners’ copyright laws are more balanced. These industries include software developers, internet search and hosting providers, manufactures of communications technology hardware, and scientific research firms.[1] We define balance as having limitations and exceptions that are open to the use of any type of work, by any user, or with a general exception that is open to any purpose subject to protections of the legitimate interests of right holders. Econometric tests presented below demonstrate the positive relationship between this openness of copyright exceptions and returns to foreign affiliates of U.S. firms in these industries.

Last year, we submitted comments to USTR regarding negotiating objectives for US-Mexico-Canada Agreement in which we recommended that U.S. negotiators seek a copyright provision that balances the interest of rightholders and users of copyrighted works. We pointed to the U.S.-proposed language in the Trans-Pacific Partnership that required countries to try to

endeavor to achieve an appropriate balance in its copyright and related rights system, among other things by means of limitations or exceptions … including those for the digital environment. [Art. 18.66]

This language is a good first step towards more binding language concerning copyright limitations. Other comments submitted to the docket that called for language promoting balance in copyright were submitted by the Computer and Communications Industry Association, the Internet Association , the Consumer Technology Association , Re:Create and Engine, among others.

Unfortunately, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement does not include a copyright balancing provision. By excluding the provision, the United States loses an opportunity to promote the interests of firms in some of its most innovative sectors. I hope that if the text is amended during the implementation process – as some have suggested may be necessary to assure Congressional ratification – that such language could be included in a final text.

U.S. Multinational Firms Benefit When Host Countries Have More Balanced Copyright Provisions

This section presents research from a PIJIP white paper, “The User Rights Database: Measuring the Impact of Opening Copyright Exceptions.” PIJIP’s User Rights Database tracks changes to copyright limitations over time in multiple countries. It is based on a detailed survey completed by legal scholars around the world. The survey defines “law” broadly, explicitly including “all authoritative, published rules or interpretations,” including “statutory law, administrative regulations or directives, decisions by courts, enforcement agencies or others.” It asks a series of questions about the openness of 20 separate copyright limitations often found in national laws (i.e. – the quotation and education exception). We code the answers and use them to derive an openness score for each country in each year. The survey instrument and coding process is described in more detail in our white paper.

Our surveys and data are publicly available under a creative commons license.

One section of our paper uses the openness score to illustrate the positive relationship between copyright openness and the returns to the foreign affiliates of U.S. multinational corporations. It uses industry-level data on foreign affiliates of American Multinational

Enterprises, taken from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.[2] We collected data on three variables of interest: net income, total sales, and value added for affiliates in the Scientific and Technical Services sector between 1999 and 2014. These are the industries under the two-digit NAICS code 54, which include research and development services and computer systems development, among others.[3]

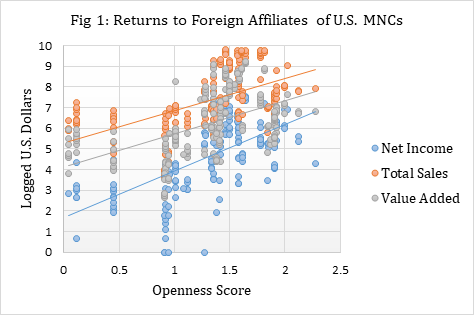

As demonstrated by Figure 1, foreign affiliates of U.S. firms in this sector tend to have greater net income and total sales when the host countries have greater openness of copyright user rights. They also report higher value-added.

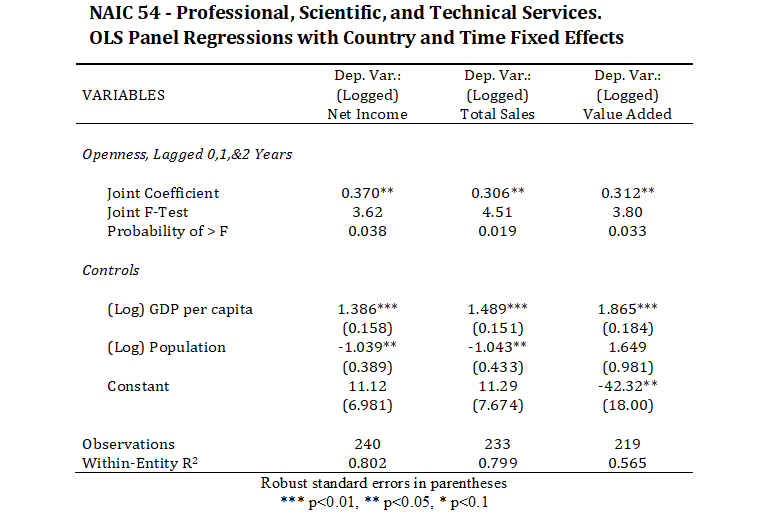

To control for other factors that ought to affect industry returns, we run a series of panel regressions testing the relationship of openness to each of the three dependent variables: net income, total sales, and value added. In these regressions, GDP per capita controls for the wealth of the local market, and population controls for its size. Fixed effects control for country and time. The results, presented in the table below, show that the positive relationship between openness and industry performance is significant and robust to the inclusion of controls. The coefficients suggest that a one-unit increase in the openness score is associated with a 37% increase in industry net income and 31% increases in both total sales and value added.

The coefficient on our openness score is positive and statistically significant at the 99% level of confidence for each of the three tests. The coefficients on the control variables are also positive and significant, as expected, and R2s between 0.67 and 0.79 indicate a good overall fit. Taken together, the results indicate that openness is associated with greater returns to foreign affiliates of U.S. firms in these industries, even when controlling for other factors that also affect returns (wealth, market size, and time).

FOOTNOTES

- For a more complete list of industries that rely on copyright limitations, see the CCIA white paper, Fair Use in the US Economy. The 2010 version has the most complete breakdown of industries that rely on limitations , and the 2017 version gives the most up-to-date estimates of these industries’ contributions to the U.S. economy. Both are available at http://www.ccianet.org/library/resource-library/white-papers-and-reports/

- The data is available at the two-digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) level of disaggregation. The BEA tables are available at https://www.bea.gov/international/di1usdop.htm.

- NAICS identifies industries at different levels of disaggregation, which are indicated by the number of digits. Two-digit classifications are very broad (i.e. – NAICS 54: “Professional, scientific, and technical services”), and more precise classifications are nested underneath and indicated by more digits (i.e. – NAICS 5415: “Computer systems design and related services”). For data on the activities of foreign subsidiaries of U.S. MNEs, the Bureau of Economic Analysis only provides data at the two-digit level of disaggregation.