Cauê Oliveira Fanha

Permanent Mission of Brazil to the WTO

Click here to download PPT

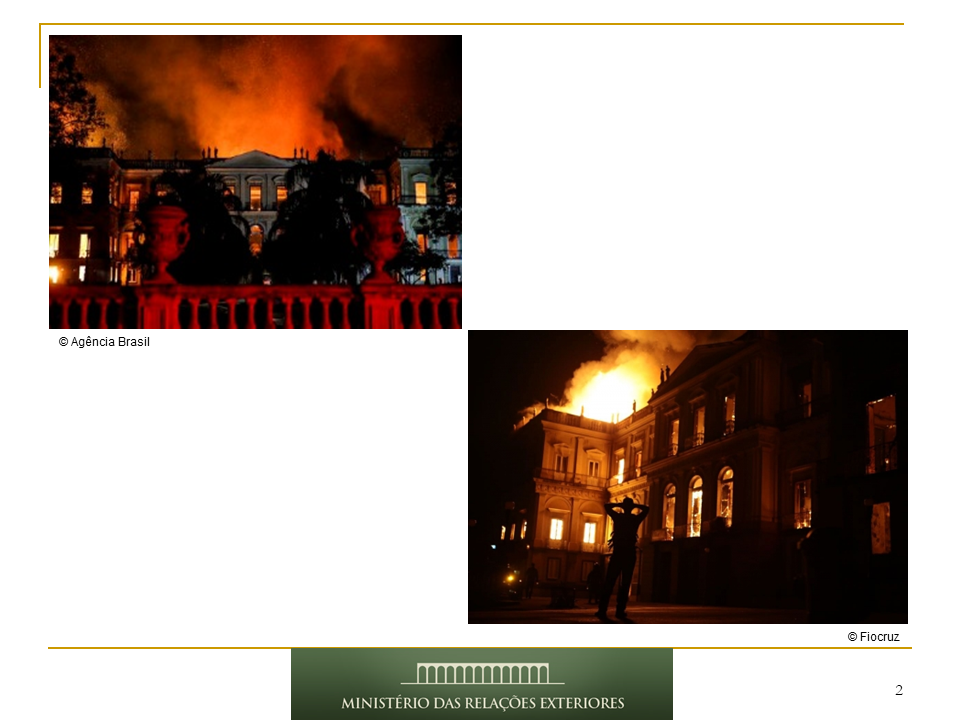

In September 2nd, 2018, Brazilians followed with shock news of the fire at the National Museum. Most of the scientifically and culturally invaluable artifacts were destroyed. 200 years of memories and science went up in flames. Initial estimates indicate that 90% of collection was lost, an irreparable damage to our culture and knowledge.

The National Museum is the oldest scientific institution in Brazil. It was founded in 1818, three years before our independence from Portugal, and its collection was initially formed by donations from the Imperial family and private collectors. In 2018, it had the largest collection of natural history in Latin America, with over 20 million items. The collection also covered areas such as biology, paleontology and ethnology.

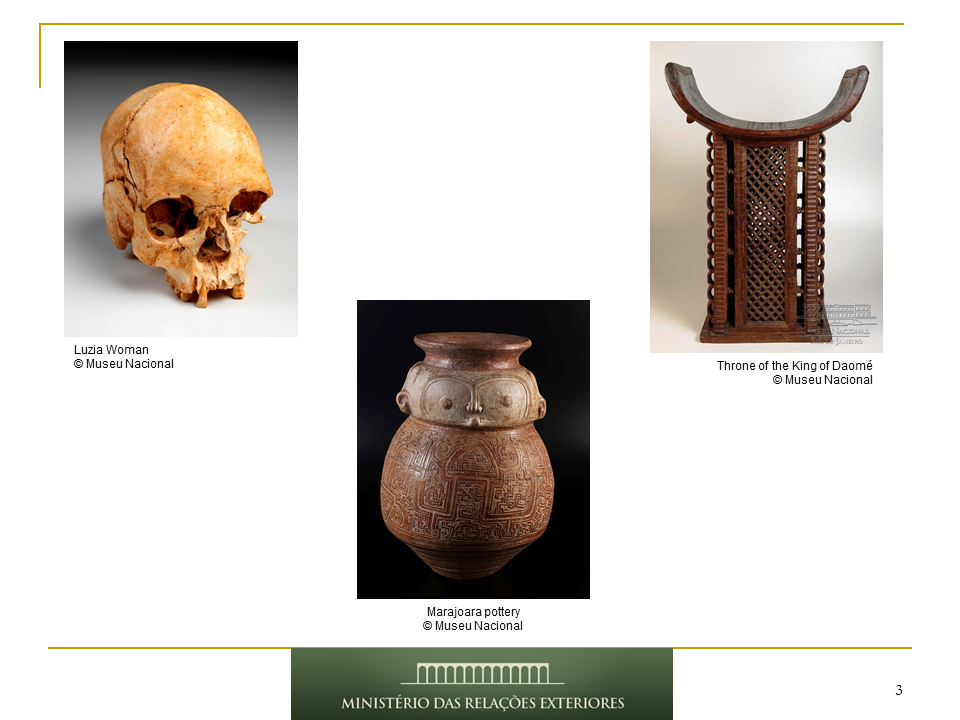

Despite being a country with a relatively young written history, Brazil has been populated for a long time. In this slide you’ll see some of the artifacts that were in the National Museum in the day of the fire.

The image on the left shows the skull of the Luzia woman, estimated to be around 12 thousand years old. Archeologists believe the young woman may have been part of the first wave of immigrants to South America.

In the center, this funeral urn was made by the Marajoara indigenous people, who lived in the Amazon region. It was estimated to be one thousand years old. The Marajoara were a sophisticated pre-Columbian era society which developed in the mouth of the Amazon river. They were one of the first indigenous peoples to develop agricultural techniques.

On the right you see the 18th century throne of a king from Daomé, nowadays Benin, a gift from the Ambassadors of King Adandozan. It was in the collection of the Museum since its inauguration in 1818.

Additionally, 36 thousand books from the Francisca Keller Library were destroyed.

Many type-specimen of insects were destroyed. The type is the basic specimen from which a whole category of an animal or plant is described.

One of the most significant losses was the collection of the German ethnologist Curt Nimuendajú. Born Curt Unckel in the German town of Jena in 1883, Mr. Nimuendajú was adopted by members of a Guarani tribe in the state of São Paulo who gave him the new name, which means “one who created his own place.” He died among the Tikuna people in 1945, leaving behind notes, letters, expedition journals and a map he created one year before his death detailing the location and languages of the groups he had come across.

The original map was copied and an adapted version was published by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. But there was another map, a unique one, where he made corrections, lost in the fire. The indigenous collection included audio recordings of indigenous leaders who died several years ago, and writings about languages that have long become extinct, including Mura and Tupiniquim.

Fortunately, not all was lost.

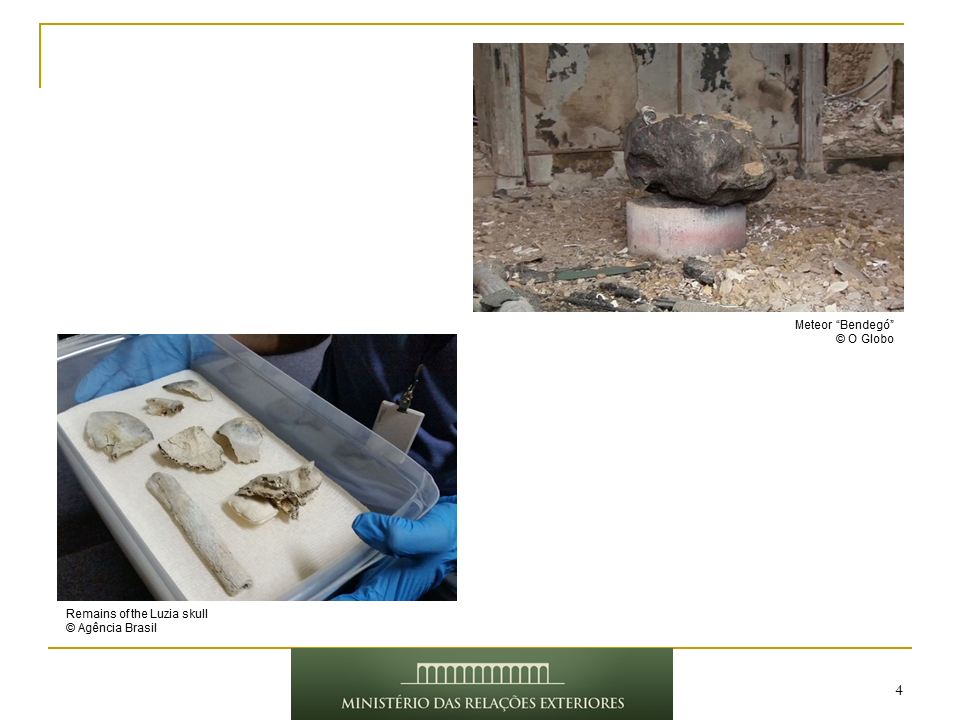

As you see in the picture, around 80% of the skull of the Luzia woman was recovered.

The meteor Bendegó also resisted the fire. The meteor was discovered in 1784 and at the time, it was the second largest meteorite in the world.

In order to maximize the number of artifacts recovered, all the debris from the fire were separated and, as of now, a team of archeologists is carefully analyzing the remains in order to rescue any artifact. We expect this activity to last up to 12 months.

Furthermore, UNESCO sent a team of experts to assist in the recovery efforts. The team has a long experience in safeguarding and recovering damaged cultural heritage, including in Syria and Lebanon.

Governments and museums from more than 10 countries offered assistance, in the form of financial aid or the supply of duplicated copies of books.

Editors such as Cambridge University Press donated many books, while Princeton University Press is exploring ways to make available digital copies of rare books to the Francisca Keller Library. So far, 10% of the original collection was recovered.

We are very grateful for the assistance provided, which underlines the importance given to the preservation of cultural heritage by countries from every level of development.

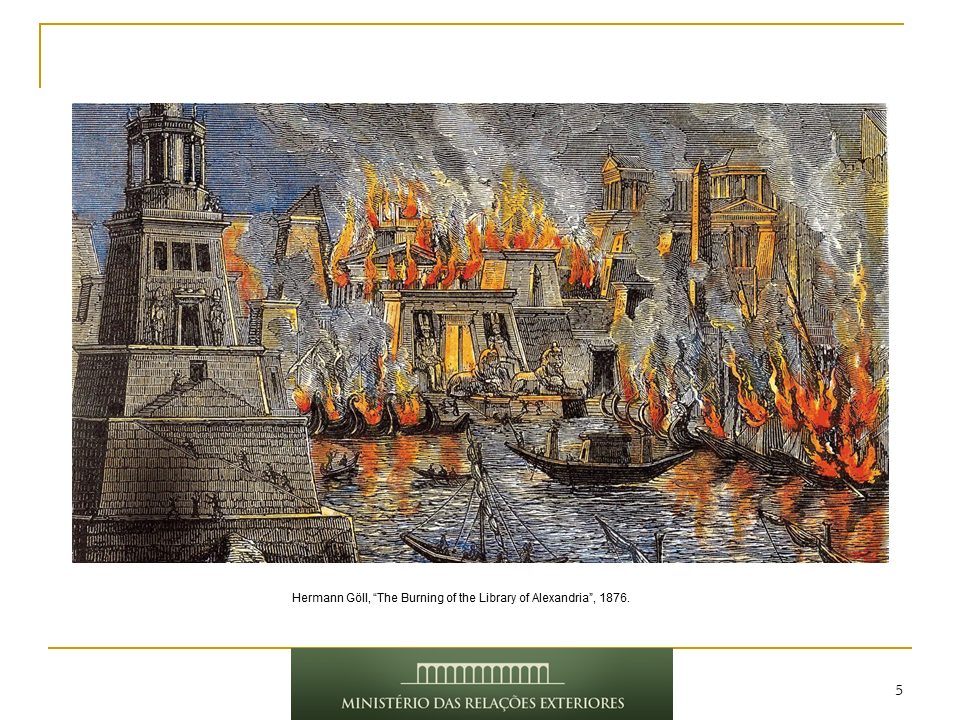

In the image you see a work by German artist Hermann Göll showing the burning of the Library of Alexandria.

The modern term “museum” comes from “Mouseion of Alexandria”, which included the Library of Alexandria. The mouseion is the homes of the Muses, the goddesses of literature, science and the arts. So you see that it is common that Museums are simultaneously libraries and archives, something which has come up in our discussions at the SCCR.

Fires at museum and archives are an unfortunately recurrent event in mankind’s history. From the Library of Alexandria to the National Museum of Brazil, much of human history was damaged or lost due to those incidents.

One month after the National Museum tragedy, a fire at a depot of the Deutsches Museum in Munich damaged many artifacts.

There are many other examples in history, such as the burning of the US Library of Congress in 1814 or the fire in the National Library of Peru of 1943.

So what can we do to minimize or eliminate such tragedies, apart from safety measures against fires?

As was mentioned by professor Crews in the last session of the SCCR, our unfortunate experience illustrates the importance of preservation activities by Museums and Archives.

In this sense, there are many initiatives in Brazil to digitalize the collections held by Museums and art institutes.

For instance, the São Paulo Pinacoteca is the art gallery of the State of São Paulo. They recently adopted a new preservation policy and reviewed their digital archives in order to ensure that every work physically available is preserved in a digital format.

The Pinacoteca registers all the main information related to the work, such as author, title, date, size, origin. They also generate high-resolution images of the works in the catalogue. When possible, authors are interviewed and they are invited to comment on the technical specificities of their work. All this data is stored in a digital format and the back-up is preserved in a different launch.

Google Arts launched a digital visit to the National Museum based on images provided by the National Museum.

All those efforts aiming at the preservation and recovering of cultural heritage can only be done if the catalogues of museum and archives are comprehensive and duly preserved. In some countries, legislative action may be needed in order to enable those acts.

Article 6 of the recently adopted EU directive on the single digital market is a good example. It provides an exception for the preservation of cultural heritage allowing cultural heritage institutions to make copies of any works or other subject matter that are permanently in their collections, in any format or medium, for purposes of preservation.

Of course, the copies for preservation are useful to restore the memory of the collection. However, none of this replace the physical experience of the original work in the museum.

Let me end the presentation with a statement made by an official in the aftermath of the tragedy: “The Francisca Keller Library today lies in ashes, but it is not dead. A library only dies when there are no more readers and we have readers. Now we need books.”