Robert Jeyakumar, Malaysian Academic Movement

Reposted from Education International, Link (CC-BY)

I woke up in Budapest on a fine summer morning to deliver a lecture using materials I had prepared in Malaysia in accordance with copyright exceptions allowed in Malaysia. Just before the lecture, I was informed that my materials did not conform to copyright laws in the EU. Dismay! This was just the beginning of my series of lectures, I still had to deliver lectures in Poland, the Czech Republic, Germany, and the UK. I began to wonder how many versions of the lecture materials I had to prepare. Cross-border education in the 21st century should allow greater mobility and copyright exceptions for both printed and digital works, no?

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Asia-Pacific Regional Seminar was held in Singapore on the 28th to 30th April 2019. I took part in the event as a member of the EI delegation to express our teacher concerns on copyright issues. Among the objectives of this seminar was to gather views from teacher unions on copyright exceptions for education. In 2017, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) commissioned a study to analyse copyright laws in the 191 WIPO Member States. One of the main objectives was to understand how copyright laws create barriers or support the work of teachers and how countries protect educational exceptions from contractual and technological overrides. Education International advocates that when the law allows educators to use digital works, they should not be prevented from doing so; however, this remains a challenge for educators from most WIPO member states.

During the seminar, WIPO provided several questions to be answered by representatives of states and civil society groups. They included which types of materials are used by educators, which educational or research activities they undertake and whether they engage in cross-border activities on online learning platforms. Topics that were superficially addressed were digital locks and the use of digital works that are often neglected in national copyright laws. The following paragraphs are from notes used by teacher groups to answer the three fundamental questions on copyrights and their impact on teaching and learning.

Diversity of teaching materials and activities needs to be considered

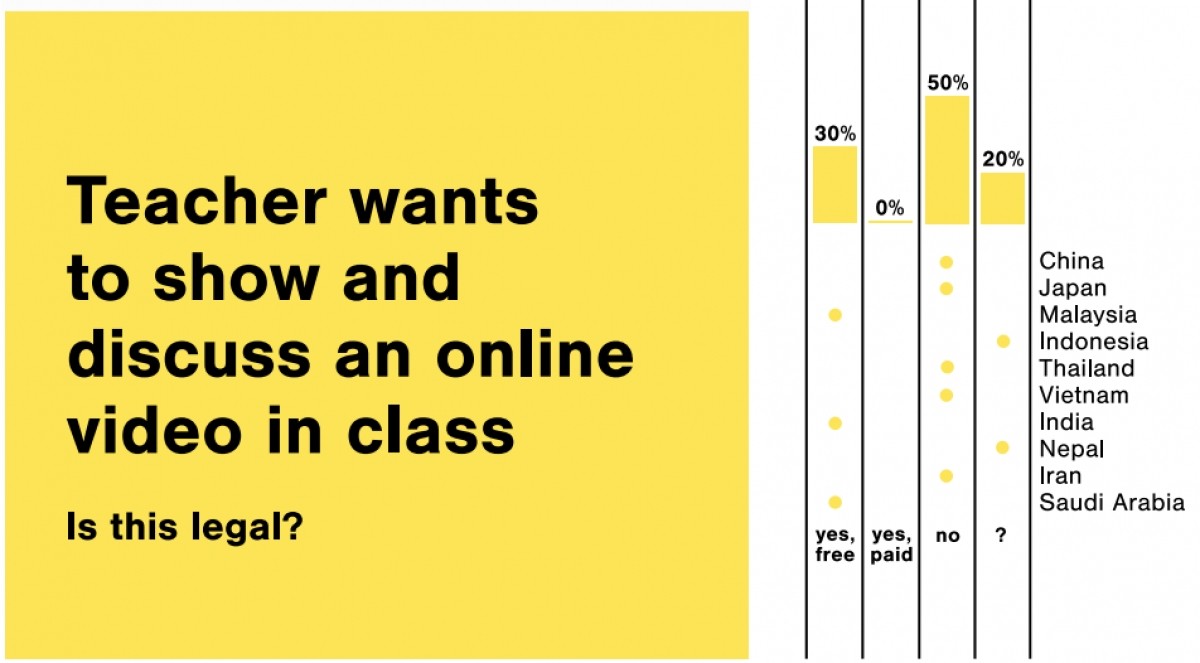

The role of the teacher is to make education informative and engaging. Hence, teachers use materials accessible to them for teaching in and out of classrooms. The classroom itself should not be inferior to the living room of a student. If a student can watch a YouTube video from her SmartTV at home, why can’t her teacher show a YouTube video in class? As can be seen in the infographic below, these are big challenges in the Asia-Pacific region. In addition to the traditional act of making copies of printed materials for teaching, teachers are increasingly using digital works in education. These include online videos from YouTube or social media sites, taking a picture of a diagram in the textbook and sharing it with student groups via Instant Messaging Apps such as Whatsapp. The nature of teaching and learning in the age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution has changed dramatically; the current students who are “digital natives” learn more effectively in a hybrid learning ecosystem that capitalizes on both physical and digital tools.

Digital locks are a major barrier to teaching and research

Technical Protection Measures (TPM), also known as Digital Locks, may create obstacles in countries where the copyright laws do not foresee the right to use materials protected by such digital locks when the use is made under an educational exception. For example, Malaysia has a very broad educational exception, which covers many of the different educational activities of teachers, but the exception is of little use with regard to digital materials if the materials are protected with digital locks. In such cases, the digital locks may simply override the education exception. The circumvention of TPM blocks the exercise of the right to education copyright exceptions in Malaysia.

Cross-border research and teaching activities are a reality!

The future landscape of education is one that is mobile and beyond national boundaries. Relating to my own experience delivering lectures abroad, teachers may experience similar problems while giving lectures based on their own material in foreign countries, as the works used which had the copyright cleared in the home country may not be cleared abroad. Teachers and students may not be able to collaborate across borders because their copyright laws differ and, therefore, may not be able to exchange materials or us them as required for collaborative work (e.g. adding subtitles, doing translations, etc.). Several means of communications, including email, instant messaging and cloud services, are also not yet included in copyright exceptions.

Teachers and learners may face problems in obtaining material from abroad because of geo-blocking of online content. Educational institutions developing distance learning courses may not be able to offer their courses across borders because they cannot clear the rights on all the materials used in every country of the world. The web streaming of an academic conference also raises copyright obstacles because the educational institution cannot universally clear the rights of the copyrighted materials shown in the conference. The use of copyrighted material may be subject to a license, and the license may not cover the territory where the teachers want to use the material. Such modern educational practices are increasingly common in academia in Malaysia and in the Asia-Pacific region.

These restrictions on education raise an overwhelming need to relook at the copyright exceptions for education. This is essential for quality teaching and research as recognized in the internationally ratified UNESCO/ILO recommendation concerning the status of teachers and the UNESCO recommendation concerning the status of higher-education teaching personnel, teachers need to have the academic freedom and professional autonomy to choose and adapt teaching and learning materials without being restrained.

We need an international instrument such as the draft Treaty on Copyright Exceptions and Limitations for Educational and Research Activities (TERA) to promote national level reforms and establish minimum standards as well as legal clarity for cross-border education collaboration and exchange. Therefore, my organisation, the Malaysian Academic Movement (MOVE) voted for a global teacher union resolution on this topic at EI’s recent World Congress in Bangkok. The current educational realities are complex, and a balanced approach to copyright is urgently needed; one that will free teachers to do what they do best – Teach without Restrictions!