Reposted with author’s permission from the Kluwer Copyright Blog.

Link to original post on Kluwer.

Jacob Flynn (Monash University), Rebecca Giblin (Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia), and François Petitjean (Monash University)

Copyright’s underuse hypothesis is simple: that, unless publishers are assured of exclusive rights in older works, they won’t continue to invest in making them available. This of course contradicts a core tenet of classical economic theory, that investors will continue to produce copies of books (or anything else) so long as they can expect to get back more than they put in. Despite that contradiction, the underuse theory played a key role in securing the 1998 US term extension to life plus 70 years. It wasn’t the main driver: that was clearly the EU’s own adoption of life + 70, which would not be enjoyed by the owners of American works unless the US extended its own term to match. But it played a key supporting role, used to discount the value of the public domain and thus strengthen the case for extension. Since then, the US has enthusiastically exported the longer term around the world via free trade agreements.

The underuse hypothesis has begun to be empirically tested over the last decade, most comprehensively in a series of studies by Professor Paul Heald. These studies have consistently found that works that are in the public domain are more available than similar works that are still under copyright, casting the theory into considerable doubt. But it has some limits. Each study before now was carried out exclusively in the US. And, since they were limited to a single jurisdiction, they could only analyse availability of similar works by copyright status – such as books published before 1923 (which are all in the US public domain) with books published after 1923 (which, if renewed, were still under copyright).

We have now carried out the first international test of the underuse hypothesis – across the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. And, since we were analysing availability of works across jurisdictions, that enabled us, also for the first time, to examine how the availability of identical works differed according to copyright status.

WHAT WE DID

We began by identifying all authors in the Oxford Companions to Literature who had died between 1962 and 1967. This resulted in a list of over 200 authors, including such notables as Aldous Huxley, Sylvia Plath and Ian Fleming. All books by these authors were in the public domain in NZ and Canada and under copyright in Australia. They could have either status in the US (depending on whether the copyright owner had renewed their original term).

We then collected data about the availability of titles by those authors in each jurisdiction. We were interested in the extent to which commercial publishers (as distinct from volunteers) were making them available as ebooks for libraries to license. We collected this data from OverDrive, the world’s largest ‘elending’ aggregator, which facilitated some 185 million ebook loans last year alone. For US titles, we also checked their individual copyright status via the Stanford Copyright Renewals Database. We then did some algorithmic jiujitsu to link title records across jurisdictions so that we could understand differences in how the titles were being licensed.

SOME KEY RESULTS

1. 59% of the sampled authors had no ebooks available for libraries to license in any of the four countries – regardless of copyright status

Authors with zero ebooks available included five Pulitzer Prize winners (Van Wyck Brooks, Russel Crouse, Esther Forbes, Frank Luther Mott and Elmer Rice). Commercial publishers made at least one ebook available in at least one jurisdiction for the remaining 92 authors.

30 (33%) of these had only one title available. A number of prolific and well-known writers had just a fraction of their work represented. For example, just seven of e e cummings’ 30 books were available to libraries for elending. This provides further evidence that the economic value of most works ends earlier than their copyright terms – and that this can be so even where cultural value remains.

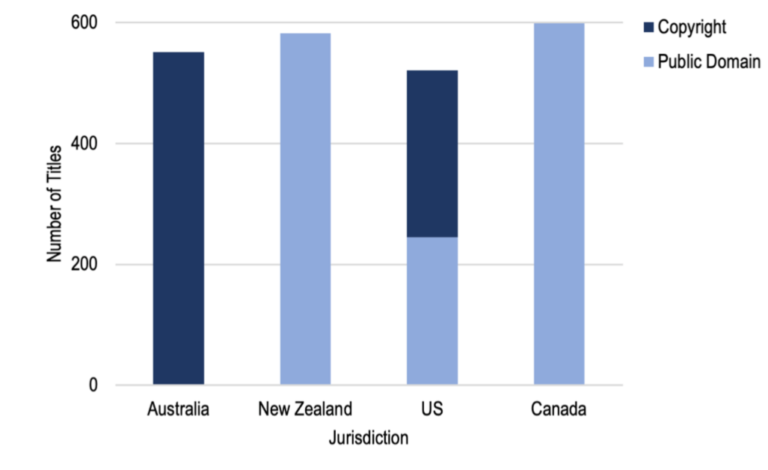

2. More titles were available in the public domain countries

In related work, we had previously created a much larger dataset of almost 100,000 books licensed via OverDrive. There, we found very high degrees of overlap in the books that were available in two pairs of countries: Australia with NZ, and the US with Canada. These results provided a baseline for the degree of similarity we would expect for each pair of jurisdictions. To the extent that greater differences are found, they are more likely attributable to copyright status.

In the control sample Canada had 0.6% more titles available than the US, but in the new public domain sample it had 15% more. NZ had 0.7% more titles than Australia in the control dataset, but 5.6% more in the public domain sample. We also observed that NZ had 10.5% fewer books than the US in the control, but 11.7% more in the public domain sample.

These results are particularly striking given the US’s status as the world’s most valuable book market, with revenues estimated at over US$26 billion in 2017. NZ had access to more titles in the public domain sample despite its book market being worth a fractional 1% of that amount — and Canada had more still. The strong showing by the two public domain countries contradicts the underuse hypothesis, demonstrating a willingness by publishers to invest in making derivative ebooks available in the absence of exclusive rights.

3. Where books were missing, it was overwhelmingly where they were under copyright

Because we were able to identify each distinct title appearing in our sample, and to ‘match’ them across jurisdictions, we were able to detect where books were and were not available. To better understand the direction in which underinvestment was occurring, we investigated which of the sampled ebooks were available in a copyright jurisdiction but unavailable in the corresponding public domain jurisdiction (and vice versa). If the underuse theory is correct, we would expect to find titles more available in copyright jurisdictions than where they are in the public domain.

We found no ebooks available in Australia (where they would be under copyright) but not in NZ (where they would be in the public domain). However, we identified 12 ebooks that were available in NZ (public domain) but not in Australia (copyright). These included titles by notable authors such as C S Lewis, William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor.

In North America, we identified 101 titles available in Canada but not in the US. In the other direction, 11 titles were available under copyright in the US but unavailable in Canada, and 27 titles were available in the US public domain but not available in Canada, where they would also be in the public domain.

These results suggest that, at least for older, culturally valuable works with low fixed and marginal costs of production and distribution, underinvestment may flow from the existence of copyright rights, rather than from their absence.

This is further evidence that, just because someone holds the rights to a work, that doesn’t mean they’ll actually exploit them. In fact, they might be standing in the way of another investor who wants to do so. If we’re going to solve copyright’s biggest challenges – its failures to get creators paid and keep culture available – then we need to think much more carefully about how those rights are allocated in the first place.

The full written paper has more detail about our method and the rest of our results, including a sub-study comparing commercial availability in the US to non-commercial availability via Project Gutenberg.

What happens when books enter the public domain? Testing copyright’s underuse hypothesis across Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada by Jacob Flynn, Rebecca Giblin & François Petitjean has just been published in the University of New South Wales Law Journal. This blog post draws from that paper, and all sources can be found within it.