In 2017, PIJIP released the User Rights Database, a novel, survey-based dataset, which measures changes to countries’ laws on copyright exceptions over time. Last spring we have added three additional countries to the dataset – Canada, Mexico and Taiwan. This post introduces the new data and discusses how it compares to the data from the original set of countries.

The User Rights Database

One of PIJIP’s ongoing research projects is the User Rights Database. This is a novel, survey-based dataset, which measures changes to countries’ laws on copyright exceptions over time. It is meant to be tool for further econometric research, and it is available online in both coded and human-readable form. We have used it to study changes in the openness of research exceptions over time, defining openness as the degree to which a copyright exception can be utilized for any purpose, use (aka activity), work or user.

We developed the User Right Database by surveying legal experts around the world – many from the Global Network on Copyright User Rights – and coding their answers.[1] The survey was comprised of 129 questions, grouped into 20 categories. Respondents were asked if their country’s law had an exception for each category in in 1970, and then to give the year and a description of legal changes between 1970 and the present. The survey also asked for qualities of the exception if one existed – for instance, whether the exception was open to any user, whether it was open to any purpose, or whether it was open to commercial uses. To capture possible ambiguities in the law, respondents answered questions on a four point scale running from “Cleary Not Included” to “Clearly Included.” These answers were cite checked and then coded on a 0 to 3 scale. (The complete survey is available here.)

The database is more fully presented in The User Rights Database: Measuring the Impact of Opening Copyright Exceptions, by Sean Flynn and I, which we prepared for the Fifth Global Congress on IP and the Public Interest.

The New Data

The User Rights Database originally covered 21 countries, 10 of which were classified by the World Bank as Middle Income and 11 as High Income. Today we are announcing the addition of survey results from three additional countries:

- Canada

Survey Respondents: David Fewer and Lucie Guibault

Written Response | Coded Response - Mexico

Survey Respondent: Andrés Izquierdo

Written Response | Coded Response - Taiwan

Survey Respondent: Jyh-An Lee

Written Response | Coded Response

How the New Data Compares to the Data from the Original Set of Countries

Our data shows that copyright exceptions in our set of countries have been becoming more open on average over time. This assertion is based on our Openness Score, a variable based on 76 survey questions to serve as a broad measurement of openness of countries’ copyright exceptions.

Our data also shows that there is a gap between openness of copyright exceptions in high- and middle-income countries. The addition of three new countries does not change this finding.

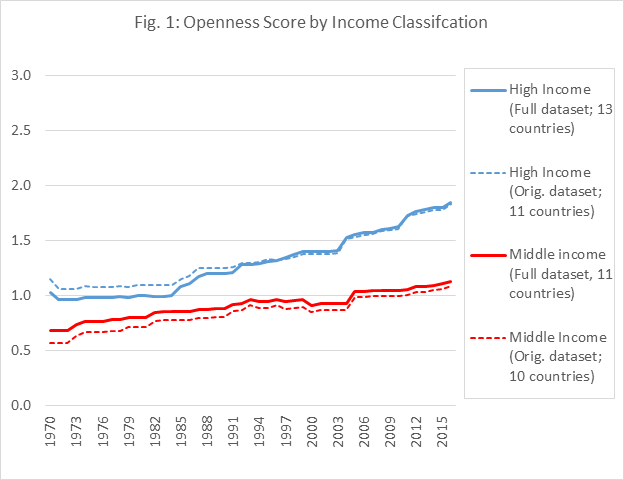

Figure 1 shows the growth of the Openness Score for the countries disaggregated by income group, both before and after the introduction of the three new countries to the database. The blue lines show the average score each year for the group of high income countries – both the 11 countries in the originally released dataset (dashed line) and the full dataset, with Canada and Taiwan added (solid line). The red lines show the same for the middle income countries.

The overall trends are clear, and are largely unaffected by the addition of the three new countries to the dataset.

Taking a closer look at the trends in the openness score of each of the three countries, certain trends stand out.

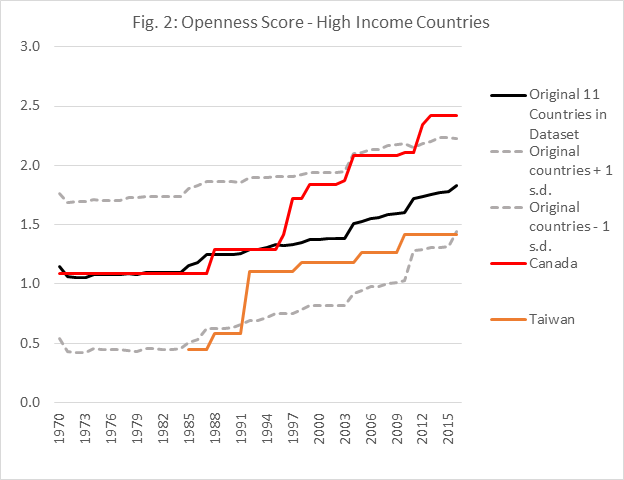

Figure 2 compares the growth of the openness score in Canada and Hong Kong to the average growth of the original 11 high-income countries in the set.

Canada’s openness score tracks the 11 high-income country average very closely until 1997, when new copyright amendments expanded the openness of copyright exceptions for quotations, incidental uses, uses for disability access, and use by libraries. However, the score remains within one standard deviation of the average through 2011.

Canada’s openness score rises further at year 2012, becoming somewhat of an outlier. In 2012, Canada passed the Copyright Modernization Act. The bill summary states that it amends the Copyright Act to “… (c) permit businesses, educators and libraries to make greater use of copyright material in digital form; (d) allow educators and students to make greater use of copyright material; (e) permit certain uses of copyright material by consumers.” 2012 was also the year that the Supreme Court of Canada decided a series of copyright case impacting user rights, such as Alberta (Education) v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), which expanded the educational use exception to fair dealing.

Tawian’s openness score is below the average high-income country score. Before 1985, Taiwan used the imperial Chinese copyright law, which did not contain copyright exceptions. The first copyright exceptions, added in 1985 allowed libraries to provide works for research purposes, and allowed the use of speeches and performances for media reporting or private use.

Fair dealing was introduced in 1992, applying the familiar four factor test to a closed list of permitted purposes. This change is reflected in our openness score, which moves within one standard deviation of the high-income country average in 1992. Other legal changes have gradually raised the score since then, including the expansion of fair dealing into a general fair use clause in 1998. The second largest raise in the country’s openness score was in 2010, when Taiwan introduced an orphan works exception that was open to any user, purpose, or type of work, and open to commercial uses.

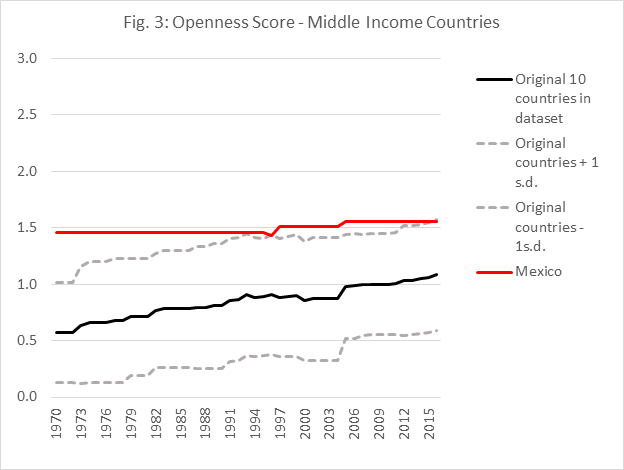

Figure 3 compares Mexico’s openness score to the average of the other 10 countries in the dataset. It has been substantially above the average for middle income countries for the whole period. This is partially based on a strong general exceptions and quotation, education, research and library exceptions. The openness score has only minimally increased over the time period. In 1996 the quotation right became applicable to quotation in new types of works, including the free display of excerpts or snippets online. In 2005, further amendments permitted more open uses for disability access.

Conclusion

Data from the User Rights Database shows that copyright exceptions have been growing more open over time, that wealthier countries tend to have more open exceptions than poorer ones, and that the gap is growing. Data from three new countries does not change these three observations. I invite the reader to take a closer look at the survey data at infojustice.org/survey

The database is an ongoing PIJIP project. We hope to find more experts respondents in order to expand the number of countries that are covered. Please contact me at mpalmedo@american.edu if you would like to complete the survey for your country).

[1] I wish to thank the attorney-respondents who completed the survey: Beatriz Busaniche, Kimberlee Weatherall, Enyinna S Nwauche, Allan Rocha de Souza, David Fewer and Lucie Guibault, J. Carlos Lara, Hong Xue, Marcela Palacio-Puerta, Taina Pihlajarinne and Anette Alén-Savikko, Jyh-An Lee, Shamnad Basheer, Pankhuri Agarwal, Tatsuhiro Ueno, Ayuko Hashimoto, Heesob Nam, Andrés Izquierdo, Marco Caspers, Miguel Morachimo, Teresa Nobre, Daniel Seng, David Tan, Zuzana Adamová, Caroline Ncube, Simon Schlauri, Jyh-An Lee, Maksym Naumko, Andriy Bichuk, Rami Olwan, Peter Jaszi and Nhan T.T. Dinh.