Mike Palmedo. Post originally published by the BU GDP Center, Link

All United States Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) signed in the past 20 years have required trading partners to enact intellectual property (IP) laws that are stronger than those required by the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

In pharmaceutical markets, these “TRIPS-Plus” rules enhance the monopoly power of branded pharmaceutical producers, extending the period they have exclusive markets, free from generic competition. Nonetheless, studies that measure the impacts of particular FTAs on medicine prices have often found small effects, as the effects take a long time to become fully apparent. Studies that have instead studied the impact of TRIPS-Plus rules required by FTAs – such as patent term extensions, rules on the protection of test data – have often found significant impacts on prices or availability of medicines. However, many of the existing studies have focused on one country, and/or on a few drugs.

In a new working paper, I take another approach by focusing on one TRIPS-plus provision required by all US FTAs and demonstrating that the provision has been associated with faster inflation of imported pharmaceutical import prices in a set of 42 countries. Specifically, the research shows that the price of drug imports rose on average between 2.4 and 4.5 percentage points faster in the countries that had implemented data exclusivity than in those without it.

Data exclusivity is a form of intellectual property protection that applies to data from clinical trials. When an originator firm launches a new medicine, it must present clinical trial data to regulators to prove the product is safe and effective. When generic firms apply for marketing approval, they typically rely on the originator’s clinical trial data – allowing them to bring products to the market at a lower cost, which is passed onto the consumer in savings. Data exclusivity is a period of time, generally between 5 and 12 years, during which generic firms cannot obtain marketing approval for their products based on originator firms’ clinical data – effectively blocking them from the market. It is a layer of intellectual property protection separate from the patent right. Data exclusivity can block generic competition in the pharmaceutical market after patent expiration, or in the absence of patent protection.

The working paper utilizes a 2011 study by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) that identified laws governing clinical test data in 41 countries. Sixteen of the countries in the set are currently classified as high income countries by the World Bank and the rest are classified as middle income. The set does not include any countries from sub-Saharan Africa, but does include countries from the Americas, Europe, Asia and North Africa.

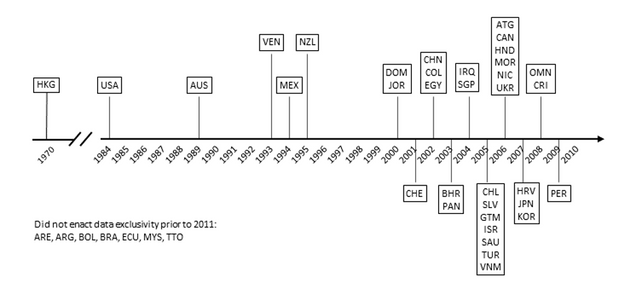

Figure 1 below shows the growing prevalence of data exclusivity in the set of countries over time. Hong Kong has had de facto data exclusivity in place since its 1970 Pharmacy and Poisons Regulations required all applicants to submit clinical data (it has since been revised to allow abbreviated generic applications after a period of data exclusivity). The US implemented data exclusivity early with the passage of the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984. Initially, there were few other countries protecting test data with terms of exclusivity – only four other countries in the set enacted data exclusivity prior to 2000. Many other countries adopted data exclusivity in the 2000s. In all, 33 of the 42 countries in the set had data exclusivity in their laws prior to the publication of the IFPMA report.

Figure 1: Timeline of Data Exclusivity Implementation

Source: Palmedo, 2021.

Some of the countries, like Chile, Guatemala and Jordan, introduced data exclusivity due to US FTA obligations that required them to do so, but not all.

Price data from the UN Comtrade database shows what happened to the price of imports when these countries implemented data exclusivity. Comtrade reports the annual value (in US dollars) and volume (in kilograms) of commercial pharmaceutical imports as recorded by border authorities. Unlike published prices, which may be subject to further discounts or markups, Comtrade reports the actual amounts of money paid at the wholesale level. Annual data is available for imports into many countries from the mid-1990s through the present and is aggregated by product class.

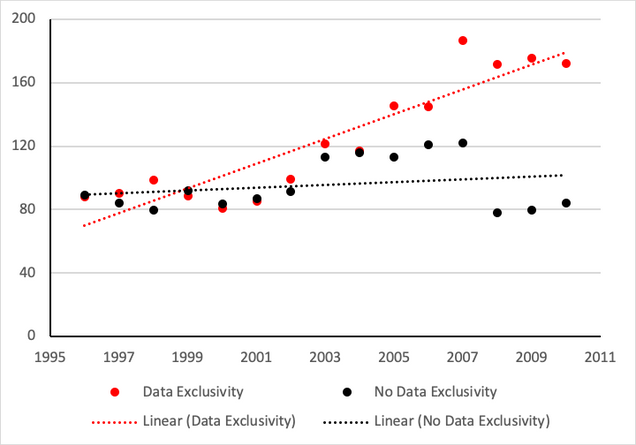

Figure 2 compares the annual average price per kilogram paid by importing countries each year, by countries with and without data exclusivity from 1996 to 2010. The price increased at a higher rate in the countries that enacted data exclusivity. Average prices in each group tended to be similar until the early 2000s and began to diverge after 2004 as more countries implemented data exclusivity in their laws.

Figure 2: Average Price Per Kilogram of Pharmaceutical Imports (USD)

Source: Palmedo, 2021.

The relationship between data exclusivity and higher price inflation for pharmaceutical imports is statistically significant and robust to the inclusion of controls. Econometric tests on this set of countries controlled for country wealth, the quantity of annual purchases, health-spending levels and the amount of spending that occurs out-of-pocket. Additional tests that more precisely measure the level of data exclusivity confirmed the original findings. Across the board, the average rate of price growth was 2.4 to 4.5 percentage points higher each year once countries implemented data exclusivity.

This finding links American trade policy to higher medicine prices abroad. Every modern US free trade agreement requires countries to enact data exclusivity, including trade agreements in low- and middle-income countries where individuals and health systems cannot afford higher prices.

The US will soon begin FTA negotiations with Kenya, a country with a GDP per capita of $1,856. It is clearly not in Kenya’s interest to pay more for drug imports, but US industry groups are advocating for the inclusion of rules requiring stronger patent and test data protection. Concomitantly, the global COVID-19 pandemic has called attention to inequalities in access to vaccines, medicines and other essential healthcare technologies. It is time to steer US trade policy away from the promotion of TRIPS-Plus IP rules that worsen this global inequality.