Introduction

Some of the most important new research today relies on text and data mining (TDM) methods. For instance researchers are using TDM to evaluate methods to fight climate change, and to monitor outbreaks of emerging diseases. Financial firms use TDM to evaluate exchange rate currency risk.

Researchers engaging in TDM need to reproduce large quantities of content from original sources, often full works, in order to produce a corpus. If they are working in collaboration with other researchers, they will need to share the corpus of reproduced works. Copyright can create barriers unless the acts of reproducing and sharing for the purpose of copyright laws are carved out.

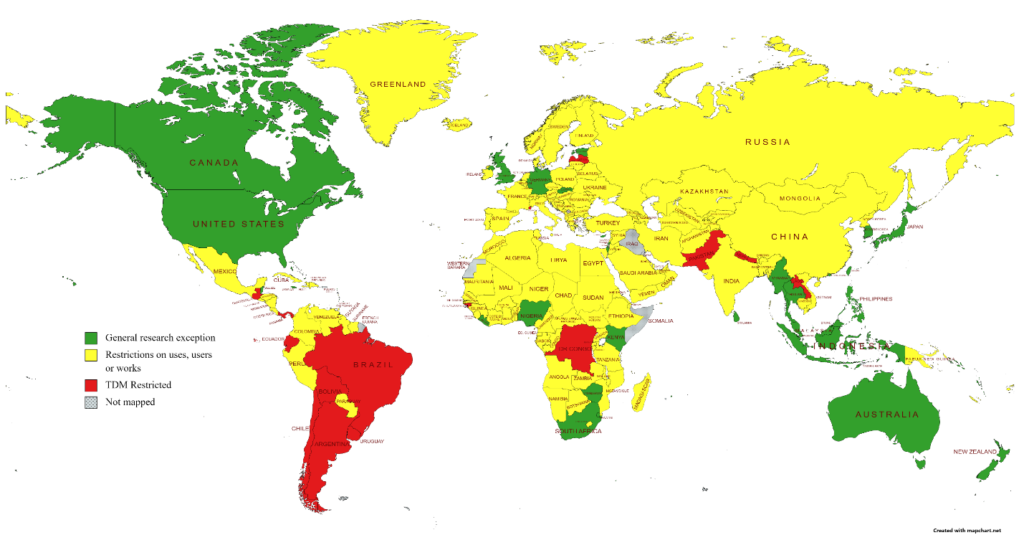

PIJIP has been reviewing copyright laws around the world. Our detailed review is available as a PIJIP working paper by Sean Flynn, Andres Izquierdo, Luca Schirru, and myself. In the paper, we “classify countries based on the degree to which they have a research exception in their law that is sufficiently open to be able to permit reproduction and communications of copyrighted work needed for academic (i.e. non-commercial) text and data mining (TDM) research.” The map below summarizes some of our findings. We find some countries have copyright exceptions that are sufficiently open to reproduce and share works for TDM. These are the countries shown in green. Some have severely restrictive copyright laws that make TDM practices fall outside of the law. These are shown in red. Most of the countries in the world fall somewhere in the middle, with copyright exceptions that allow some reproductions (and maybe sharing) but place certain restrictions on these acts. These are shown in yellow. The restrictions fall into three categories:

- Restrictions on sharing reproductions created TDM purposes;

- Restrictions on the users who can make reproductions for TDM purposes;

- Restrictions on the works that can be reproduced for TDM purposes.

A single country may have one, two or all three of these restrictions in their copyright law.

Which Restrictions Are the Most Prevalent? Where?

Recently, Duc Le, Luca Schirru, and I tallied the countries with each type of restriction. Our review uses the data from the working paper, but unlike the paper, it shows where the “yellow” countries have overlapping types of restrictions built into their copyright laws. The raw data is in this spreadsheet, which also contains each country’s GDP per capita and population.[1]

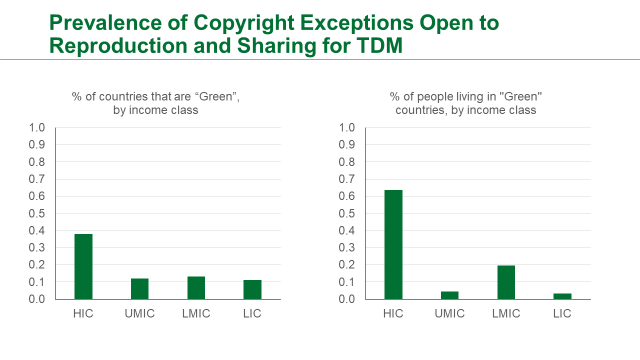

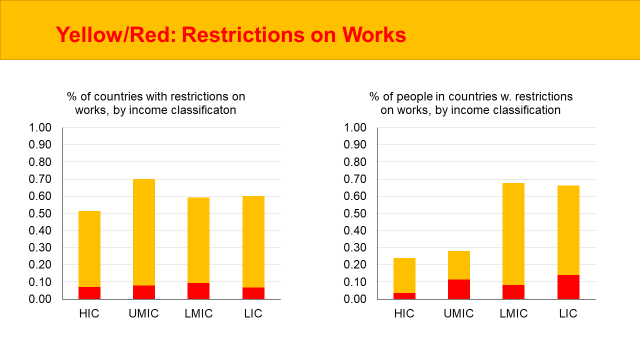

This post presents the data on copyright exceptions by restriction rather than by country. It demonstrates that wealthier countries tend to have copyright exceptions that allow TDM research, relative to other countries. The post shows the share of countries by World Bank Income Classifications that have open, restricted, or closed restrictive copyright exceptions for researchers. The World Bank Income Groups are High-Income Countries (HIC), Upper-Middle Income Countries (UMIC), Lower-Middle Income Countries (LMIC), and Low-Income Countries (LIC).

This post also shows the percentage of the world’s population that resides in countries with each type of restriction.

First, let’s look at the countries coded green on the map, that are open to reproduction and sharing for TDM. These include countries like the U.S. that have fair use in their laws – which allows the “use” rather than merely “reproduction” of a work for an open list of purposes, as long as the use passes a four-factor test. Some (but not all) countries with fair dealing for research are also coded green for broad usage rights. It also includes some countries that have other types of copyright exceptions that allow the “use” of works for TDM purposes without specific restrictions. One example is Thailand. Article 32 of its Copyright Act of 1994 (B.E. 2537) borrows from the Berne three-step test to allow any use that doesn’t harm the copyright owner:

Art. 32: An act against a copyright work under this Act of another person, which does not conflict with normal exploitation of the copyright work by the owner of copyright and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate rights of the owner of copyright shall not be deemed an infringement of copyright.

The first graph below shows that high-income countries are more likely than others to have copyright exceptions that allow TDM researchers to reproduce and share works. The second graph shows that weighting by population makes the imbalance stronger. 64% of people in high-income countries live under laws that allow TDM researchers to reproduce and share works. Only 4% of people in the upper middle, 19% of people in the lower middle, and 3% of people in low-income countries live under laws that grant researchers the same rights.

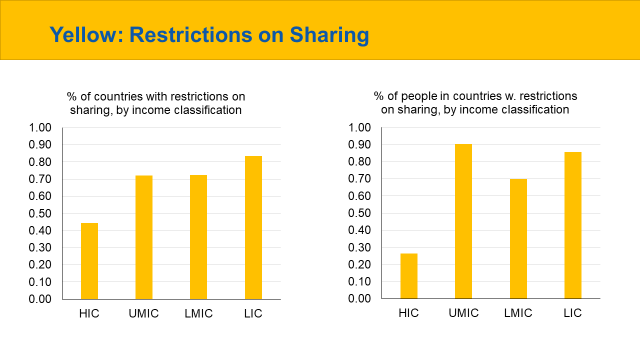

Now let’s move on to the restrictions, starting with restrictions on sharing. Often, these laws will include exceptions that allow one particular type of use of a work – “reproduction” – for TDM purposes. One example is Article 24(d) of Switzerland’s Federal Act on Copyright and Related Rights (Copyright Act, CopA).

Art. 24d. Use of works for the purposes of scientific research

1. For the purposes of scientific research, it is permissible to reproduce a work if the copying is due to the use of a technical process and if the works to be copied can be lawfully accessed.

2. On conclusion of the scientific research, the copies made in accordance with this article may be retained for archiving and backup purposes.

Slightly fewer than half of the high-income countries have this type of restriction in their copyright laws, while more than half of the countries in each of the other income groups have restrictions on sharing. Again, we see that weighting by population increases the imbalance. Only 27% of people in high-income countries live in countries where copyright law has this type of exception. The comparable figures for the other groups are 90% for people in upper-middle income countries, 70% for those in lower-middle income countries, and 86% for those in low-income countries.

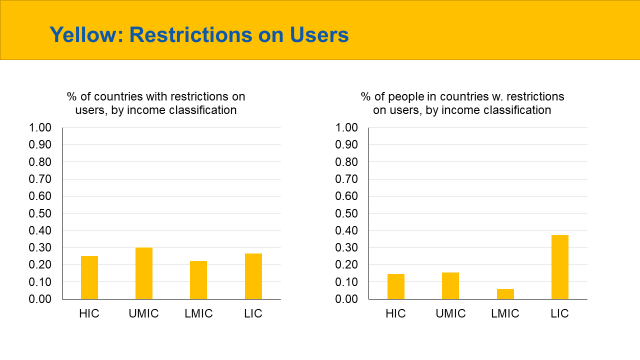

Next, we turn to restrictions on users. There are different types of restrictions that fall under this category. Some restrict use to private or personal use. An example is Article 44 of Venezuela’s Law on Copyright (1993).

Article 44: The following shall be considered lawful reproductions

1. The reproduction in one copy of a printed, sound or audiovisual work … provided that the copy is made for the exclusive personal use of the user, and is made by the interested party with his own means;

Other laws only allow institutions such as libraries or educational institutions to make copies for research purposes. An example is article 38 of Cuba’s Law No. 14 of December 28, 1977, on Copyright.

Article 38. On the Use of a Work without the Author’s Consent and without Remuneration

It is lawful, without the consent of the author and without remuneration to the same, but with obligatory reference to his name and source, provided that the work is public knowledge, and respecting its specific values:

….

d) reproduce a work by a photographic or other analogous procedure, when the reproduction is made by a library, a documentation center, a scientific institution or an educational establishment, and provided that it is done on a non-profit basis and that the number of copies is strictly limited to the needs of a specific activity;

As the graphs below show, there are fewer laws with this type of restriction. Only 30% or less of the counties in each income group have restrictions on users in their laws. In high and middle income countries, less populous countries tend to have these types of restrictions. However, 32% of people in low-income countries live in countries where the law has this type of restriction.

Finally, let’s look at restrictions on the works that are covered by the copyright exception for research. There are different ways that laws restrict the works that can be legally reproduced and shared under copyright exceptions. Often, a law will grant users the right to make reproductions for research, but it will forbid the copying of certain types of works – including full books. This is often found in private or personal use exceptions. Ghana’s Copyright Act, 2005 (Act 690) provides an example:

Section 19. Permitted use of work protected by copyright

(1) The use of a literary or artistic work either in the original language or in translation shall not be an infringement of the right of the author in that work and shall not require the consent of the owner of the copyright where the use involves:

(a) the reproduction, translation, adaptation, arrangement or other transformation of the work for exclusive personal use of a person, if the user is an individual and the work has been made public,

(…)

(2) The permission under subsection (1)(a) shall not extend to reproduction

(a) of a work of architecture in the form of building or other construction;

(b) in the form of reprography of a whole or of a substantial part of a book or of musical work in the form of notation;

(c) of the whole or of a substantial part of a database in digital form; and

(d) of a computer program, except as provided in section 16.

Some types of restrictions are more severe, restricting reproductions to only quotations or short pieces of works, or specifying a certain quantity of words that can be reproduced. In our three-color scheme, these are the countries we categorize as red, indicating that the law is too restrictive to allow research that uses text and data mining methods. One example is Article 24 of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Ordinance-Law No. 86-033 of April 5, 1986 on the Protection of Copyright and Neighboring Rights, which restricts reproductions to quotations or excerpts:

Art.24

It shall be lawful to reproduce quotations or excerpts of protected works for cultural, scientific, teaching, critical or polemic purposes, provided that the source, title and name of the author are mentioned.

Argentina provides an example of a law that places a quantitative restriction on the amount of a work that can be used. Specifically, Article 10 of Law No. 11.723 of September 28, 1933, on Legal Intellectual Property Regime, Copyright Law:

Article 10. Any person may publish, for didactic or scientific purposes, comments, criticisms or notes referring to intellectual works, including up to 1,000 words for literary or scientific works, or eight bars in musical works and, in all cases, only the parts of the text essential for that purpose.

The graph below shows that more than half of the countries in each income group have copyright laws that include restrictions on works, though few have the more restrictive type that limits reproductions to quotations or specific quantities of words. When one looks at the number of people who live in countries with this type of restriction, it clearly applies to over 60% of the people in low and lower-middle income countries, but less than a third of people in high-income or upper-middle income ones.

Conclusion

Overall, PIJIP’s review has found that wealthier countries are more likely than others to have research exceptions allowing the use of works for Text and Data Mining. This builds on earlier PIJIP research on user rights. Our 2018 report introducing the User Rights Database: Measuring the Impact of Opening Copyright Exceptions showed that wealthier countries tend to have more open copyright exceptions overall. A more recent white paper, A Novel Dataset Measuring Change in Copyright Exceptions, finds that copyright exceptions beneficial to ICT firms and educators tend to be stronger in wealthier countries.

[1] GDP per capita and population data were taken from the World Bank’s databank. In a few cases, the World Bank did not have data, so I turned to the CIA World Factbook.